The Andaman Islands are a really strange place.

Located In the Bay of Bengal between Myanmar and the island of Sumatra, just north of the Nicobar Islands, they’re really unremarkable, geographically speaking. Just another long island chain off the Asian mainland, a member of a not-so-exclusive club that also includes the Maldives, the Nicobars, Japan, and Nusantara, among others. Environmentally, they’re absolutely pedestrian; mostly evergreen rainforests with some deciduous monsoon rainforests in the far north. Ecologically, they do happen to exhibit a high degree of species endemicity; many of the small reptiles and mammals and a fair number of the plants of the Andaman Islands are found nowhere else in the world. Certainly that’s worth remarking on. But I don’t write about ecology; I write about people. And perhaps nowhere in the world will you find people as purely singular as the Andaman Islanders.

Layer 1: North Sentinel Island

In the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, the Indian Coast Guard sent a helicopter to assess the damage dealt to the people of North Sentinel Island, who lived only a few hundred kilometers north of the earthquake’s epicenter. They expected to find the tiny, low-lying island devastated, perhaps in need of aid. Instead, they were met by a lone bowman on the beach, who made it clear, via the eloquent firing of several arrows, that their help was not wanted.

Probably everybody and their mother has heard of the North Sentinelese people at this point. Everybody and their mother may have also had a knock at exoticizing and romanticizing their isolated lifestyle, especially in the aftermath of the death of an American missionary on the island in 2018 — the LA Times described them, perhaps not unfairly, as “endangered,” Smithsonian Magazine labeled the island a “small pocket of mystery in our increasingly known world,” and the Daily Mail, predictably, found a way to work the phrase “sex-crazed” into the title of their piece. All comers like to hammer home that one word, though: isolated. Separate from the broader world around them.

Put out of your mind, for a moment, the unique physical appearance of the North Sentinelese, their technologically quaint way of life, their admittedly draconian policies re: immigration and tourism. Ask the question: is it true? Or, if you’re in search of more of a challenge: in what sense is it true that these people are isolated?

My arguments in this post are pretty simple. One pokes at the more simplistic, journalisty side of the conversation, contending that the North Sentinelese and their ways should be understood in light of their place in a pre-colonial Andaman world, in which they were only one among as many as fifteen indigenous ethnolinguistic groups. The other makes a stab at a belief that, more troublingly, appears to be held in common by academic authors from a number of disciplines: that the pre-colonial Andamans were a world unto themselves, isolated from happenings in mainland Asia and elsewhere for a period as long as 70,000 years. We see this claim repeated in publications from linguistics (Abbi 2018), to genetics (Thangaraj et al 2006), to anthropology

I call this “the isolation hypothesis.” It’s simple, it’s punchy, and it’s taken some serious heat in recent years as the evidence has stacked up against it. As I will contend shortly, it’s also wrong. In fact, archaeological, linguistic, and genetic evidence indicate that Andaman prehistory is significantly more complex than has generally been conceded — and far more strongly interwoven, for good and for bad, with that of the mainland. The remainder of this post (after I finish whaling on journalists and academics like a white Uday Hussein) will be focused on unraveling this tangled thread. Where did the Andamanese come from, and when? What developments have taken place on the islands since? And what can Andamanese prehistory tell us about Asian prehistory in general?

But first:

Layer 0: The Andamans and the Andamanese

The Andaman Islands have been inhabited continuously for about as far back as recorded history goes, and insofar as we can tell it’s been by the same sort of complex of peoples that the North Sentinelese belong to. This is attested by a number of pretty old sources that describe the Andamans and their people. Sulaimān Al-Tājir (Sulaimān the Merchant, to his friends), an Arab who sailed the trade routes between the Middle East and China in the 9th century, wrote:

“Beyond are two islands separated by a sea called Andaman. The inhabitants of these islands eat men alive; their complexion is black, their hair is frizzy, their face and their eyes have a frightening aspect. They have long feet; the foot of one of them is about a cubit. They go naked and have no boats. If they had boats, they would eat all the men who passed in the neighborhood. Sometimes, ships are held up at sea, and cannot continue their journey because of the wind. When their water supply runs out, the crew approaches the locals and asks for water; sometimes the men of the crew fall into the power of the inhabitants, and most of them are put to death.”

The 13th-century Chinese historian Zhao Rukuo also wrote briefly on the Andamans and their inhabitants in his Zhu Fan Zhi (“Description of Barbarian Nations”):

“When sailing from Lan-wu-li to Si-lan, if the wind is not fair, ships may be driven to a place called Yen-t’o-man [sic]. This is a group of two islands in the middle of the sea, one of them being large, the other small; the latter is quite uninhabited. The large one measures seventy li in circuit. The natives on it are of a colour [sic] resembling black lacquer; they eat men alive, so that sailors dare not anchor on this coast.

“This island does not contain so much as an inch of iron, for which reason the natives use (bits of) conch-shell with ground edges instead of knives.”

Even farther back, the 2nd-century Geography of Claudius Ptolemy describes islands east of India and south of China inhabited by the Anthropophagi (“man-eaters”), who went around unclothed and ate huge amounts of shellfish.

Some sources describe the islands as a source of riches: Marco Polo spoke of the spices and fruits to be found there, and Zhao Rukuo of the plentiful gold. As these same sources also speak of the inhabitants as having the heads of dogs (Polo) and practicing alchemy (Zhao), it would be best to take their claims with a grain of salt (especially the apparently widespread myth of Andamanese cannibalism, which has never been supported by any firsthand account).

The Andaman Islands truly entered the historical record with the establishment of a British colony at Port Blair, on South Andaman Island, in 1790. This first colony lasted some 6 years, during which the British engaged in a number of clashes with the numerous and powerful inhabitants of the northern half of the island. They did experience a couple of diplomatic successes, though — meaning they made some overtures, in the form of friendly kidnappings, to the indigenous Andamanese living nearest Port Blair, in the southern half of South Andaman. Remarkably, this strategy appears to have succeeded in befriending said tribe, but it was not enough to save the operation. In 1796, due to persistent outbreaks of disease (probably malaria), the colony was abandoned.

The British didn’t return until 1858, when, in the aftermath of the “Indian Mutiny,” an expedition arrived to set up a new penal colony at Port Blair (there was one scientific field trip in 1840 by a Dr. Johann Wilhelm Helfer, but he was killed almost immediately after landing. Doesn’t count). Hundreds of Indian and Burmese convicts were interned there, trapped on an isolated island chain with nowhere to escape to except the open ocean and dense jungles occupied by mostly hostile natives. Although it might be more accurate to say that the Andamanese were trapped with the convicts than the other way around.

The details of what came next are ugly, and only partially of significance to the arguments presented in this post, but they should be shared regardless. The next 50 years of British colonization saw unspeakable horrors visited upon the Andamanese population. Outbreaks of diseases that the Andamanese had no immunity to depopulated entire communities. Andamanese people were massacred by the British, especially those belonging to groups that resisted colonization, like the Jarawa tribe. By the 1930s, members of the tribes that remained began to be resettled in tribal preserves, where many remain to this day. As of 2023, out of a pre-contact population of 8,000-15,000 individuals, probably 550-750 Andamanese remain. Four tribes, much reduced in size and territory, where once there were as many as fifteen.

The human cost of colonization in the Andamans was staggering. Beyond even the thousands of lives lost, an entire complex of rich and varied cultures just sort of … ceased to exist, over the course of a single human lifetime. The only people of the Andamans who still live lifestyles even remotely similar to their ancestors’ are the Jarawa and the North Sentinelese.

But certain members of the British colonial administration of the Andamans, despite their day job involving the total extermination of the indigenous Andamanese culture and people, took up a hobby of recording detailed information about the people they were steadily eliminating from the face of the Earth. Thanks to people like M. V. Portman, E. H. Man, and A. R. Radcliffe-Browne (an anthropologist), we have clear records about almost every aspect of traditional Andamanese life: food, manufacturing, infrastructure, family life, politics, religion, etc. Thanks to them, we will also never be able to gather new information from 13 of the 15 indigenous tribes of the Andamans. Mixed legacy, I guess?

Not really. They’re all burning in Hell (except maybe Radcliffe-Browne). But their loss is our gain, as we have been left with a substantially accurate series of sketches of indigenous life in the Andamans, albeit filtered through the preconceived notions of mainly British Victorian outside observers.

And man, what a picture they paint.

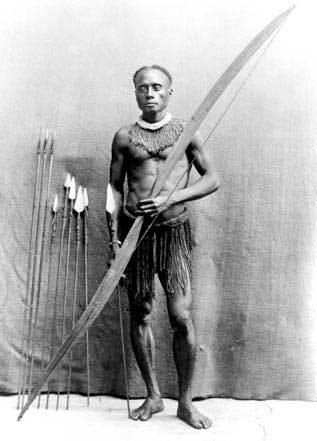

At first glance, the Andaman Islanders presented a striking image to outsiders. They are very dark-skinned, more so than almost any other ethnic group outside of Africa, and tend to be of relatively short stature, with most adult men reaching slightly under 5 feet, and most adult women being even shorter. The men and women of most tribes in pre-colonial times shaved part or all of their heads, and wore little of what a Westerner would describe as “clothing.” Really, all that means is that they (with some exceptions) didn’t cover up breasts, buttocks, or genitals. In reality, the Andamanese had a large and varied inventory of clothing items that were worn for ornamental or symbolic purposes, from the near-ubiquitous headbands and girdles that Sentinelese men still wear today, to the nakuinyage vulva-covering worn by Önge women, to the items made from dead family members’ bones among the Great Andamanese group of tribes.

Early observers believed the Andamanese to be descendants of Africans who were shipwrecked on the islands at some point in the remote past. Others assigned them to the “Negrito” group of ethnicities, which includes the phenotypically-similar Semang and Jahai of Malaysia and the Aeta, Agta, and related groups of the Philippines. Still more argued for their resemblance to Australian and Melanesian groups. Basically, for every area of the planet where people have skin darker than Pantone 139, there was a group of old-school pith-helmet racists trying to argue that the Andamanese came from there (as I’ll discuss in a later section, modern genetic evidence groups the Andamanese with the modern populations of mainland Asia).

British observers from 1858 on record that the Andamanese identified themselves with one of twelve tribal affiliations, which were generally drawn on a linguistic basis (I tend to count fifteen; the British after 1796 never managed to speak with members of the Jarawa people, and there is evidence for at least 3 distinct Jarawa dialects). These were in turn divided into two major ethnolinguistic groupings: the Great Andamanese group in the north, and the Önge-Jarawa group in the south:

Each of these tribes was in turn divided into a number of smaller subdivisions called “septs” by Portman (on the basis that the large and powerful Aka-Bea, the first tribe the British maintained regular friendly contact with, had seven). These septs were divided into a number of local groups, which generally numbered around 30 individuals and served as the basis for Andamanese social life. Each Great Andamanese tribe was identified by the name of its language, which in turn was based on the features of the area in which it was spoken or the people who spoke it. The Aka-Bea were the “spring-water people,” the Akar-Bale the “people [who live] across the sea,” the Aka-Bo the “people [who live] on the back [of the island],” the Aka-Jeru the “fast people.” The Önge-Jarawa (or Ongan) tribes, as far as we know, named themselves after their word for “person.” However, only the Önge are referred to in the literature by the name they gave themselves.

Within their own tribes, they were friendly. Within their larger ethnolinguistic groupings — the Great Andamanese on one hand, and the Ongan on the other — they were cordial with those they knew. To strangers, they were almost universally hostile, often immediately attacking outsiders who strayed into their lands. Whether these were Europeans, Indians, or other Andamanese did not appear to matter. Most accounts of interactions with the Andamanese begin and end with a hail of arrows from the jungle; for at least one of the surviving tribes, that remains the case even to this day.

They were not, as many would have it, a world unto themselves. Their material culture, their languages, and their genetic makeup provide evidence of a rich and complex history — not one spent in isolation, but one bound up in a tightly interwoven and ever-shifting regional context. In the sections to follow, I’ll review the abundant evidence for contact between the Andamanese and the outside world (yes, more recently than 60,000 years ago) — and, critically, the reasons why friendly contact ceased at some point prior to colonization. To be honest, there’s really only one major one. See if you can guess it before the end.

Layer -1: Andamanese material culture and archaeology

At the time of contact, the Andaman Islanders lived a pretty standard Stone Age hunting and gathering lifestyle in the rainforests and shallow coastal waters of their home. Some groups were adapted for inland habitation, exploiting only the rainforest for their food, while others lived on the coast, hunting, gathering, and fishing across the rainforest, mudflat, and shallow reef ecosystems. The Andamanese recognized and formalized this division; the Aka-Bea referred to inland-dwellers as Erem-taga and coast-dwellers as Ar-yɔto, and other groups had similar terms to refer to each style of subsistence. This was not an ethnic distinction, but more of an economic one; one could view the Ar-yɔto/Erem-taga split as the beginnings of a very simple class system.

On land, the bow was the preferred weapon of most Andamanese groups. These were mostly used for hunting wild pigs, an activity of which the Erem-taga were the undisputed masters, but their utility didn’t stop there. The Andamanese had a regular repertoire of at least four different types of arrow, ranging in size from the thin, light, and accurate fish arrows to the heavy and damaging but clumsy pig arrows. Bows, along with boats, baskets, and body paint, were the material objects most valued by the Andamanese, and significant care and effort went into their manufacturing and maintenance.

On the water, Andamanese Ar-yɔto groups got around in dugout canoes, with outrigger floats attached to one side to increase stability when out on the open water. There, they fished and hunted turtles and other sea creatures with harpoons. Erem-taga, when needing to cross bodies of water, would generally lash together simple bamboo rafts instead; they had neither the knowledge nor the need to construct complex watercraft.

While these are broadly the main pan-Andaman cultural features, there are a number of other common practices engaged in by a subset of the tribes. For example, scarification (arguably descended from a prior tradition of tattooing, as pigment was rubbed into the newly-made scars) was practiced by the Great Andamanese tribes, and both men and women of the Great Andamanese, Onge, and Sentinelese peoples shave their heads and bodies.

Otherwise, Andamanese material culture was honestly pretty simple. There wasn’t much in the way of clothing, besides some ornamental pieces and body paint (there’s evidence that the Andamanese thought of body paint as a form of clothing; bouncers, unfortunately, do not). They lived in huts, which were larger in the south than in the north, and moved frequently around a defined territory. Settlements were usually coastal, located near (or on) large shell middens. These massive piles of discarded shells, bones, and other garbage could reach truly ridiculous sizes, the result of generations of continuous habitation. To the Andamanese, a huge shell midden was something for a group to take pride in; it signified an enduring, multigenerational attachment between the land and the group that inhabited it.

Archaeological investigations, mostly undertaken by Zarine Cooper in the 1980’s and 90’s, targeted these shell middens around the Andamans, seeking to understand more about Andamanese prehistory by sifting through thousands of years of their trash. And man, did this archaeologist sift thoroughly. Her work is recounted in full in this really great 2002 book by the legend herself, but I’ll briefly summarize here. Cooper located 62 kitchen middens around the Andaman Islands, made surveys of 43 of them, and conducted excavations at at least 6. It’s about as thorough of an archaeological survey as I’ve seen of an area like the Andamans, and represents a solid 2 decades of work on the part of the author. If you’ve read this far into this post, stop right where you are and locate a copy. I will wait.

Anyway, the results of Cooper’s project certainly don’t disappoint. Remember how the Andamanese are an ancient unspoiled relic of the distant past, uncontacted by the outside world for upwards of 60,000 years of perfect isolation? A remnant of the first human migrations out of Africa, or M. V. Portman’s “sunken Negrito continent,” or whatever the hell people are saying these days?

Well, when the carbon dating came back, it turned out most of the kitchen middens excavated were less than 2,000 years old. The Beehive Hill midden returned a date of 1,400±100 years, compared with 1,510±100 for an unnamed nearby one. The oldest layers of the Hava Beel Cave midden were similarly dated to 1,540±110 years. The oldest was the Chauldari Midden, at 2,280±80 years old (Cooper 1990).

What the hell, right? That’s a clear mismatch between the archaeological record and this certain knowledge we hold, for some reason, about Andamanese prehistory. Some explain this as the result of sea level rise inundating older shell midden sites, or erosion along shorelines (which is pronounced in the western part of the islands). This is, in the kindest and most sympathetic possible terms, absolute horseshit. Sea levels have remained relatively stable for pretty much the last 7,000 years, and though erosion may have claimed its share of old middens, there’s still a 5,000-year chunk of the archaeological record that should be there, but isn’t.

Three options (I mean, probably. Think of however many options you want; I’m not your dad). One: some exceptional combination of erosion and sea level rise have destroyed — without exception — all middens older than 2,300 years, while leaving the majority of younger middens untouched. Or it’s a product of the relatively low number of sites excavated. In many ways, this is an explanation of last resort, to be adopted when no others can account for the data. To accept it over a competing hypothesis, I personally would need some solid evidence. Just one midden dated to those 57,700 missing years of Andamanese prehistory, I beg of you.

Two: the Andaman Islands were not settled until 2,300 years ago, at the earliest. As much as I love to rag on academic writers for making related assumptions, I have to say: absurd idea, prima facie. 2,300 years ago is perilously close to history times, in the Southeast Asian context. Considering this, a 3rd century BCE settlement of the Andaman Islands is an absolutely crazy notion. Where would they even have come from? Did they leave behind any archaeological sites back there? This kind of explanation would require a truly heroic body of evidence, and that just isn’t forthcoming.

Three (and this is the one I like): the Andamanese didn’t start building shell middens until around 2,300 years ago, when a general change in subsistence strategies resulted in the population eating significantly more mollusks than before. Before this, the Andamanese probably didn’t exploit marine resources very intensively. It’s likely that their sites would have been fewer (due to smaller populations, due to fewer available food calories) and further inland, and they would have lacked the enormous shell middens so characteristic of Andamanese sites in the historical era.

But how did this change in subsistence patterns occur? What motivated it? In archaeology, changes tend to demand corresponding explanations, especially sudden ones. Is there an explanation for the change hypothesized here re: diversification of the Andamanese into marine foraging?

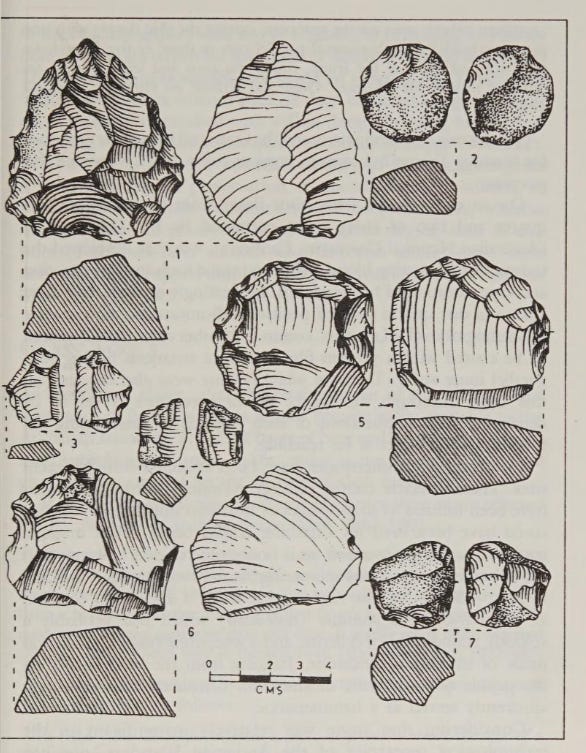

Maybe the answers can be found within the shell middens themselves. Each excavated midden has so far revealed a rich material record, from shells to bones to tools to pottery shards. The most common items found were, naturally, shells; Cooper uncovered over 7,000 unbroken shells from the excavation at Chauldari, and 173 shell fragments that showed signs of having been used as tools. These shell tools dramatically outnumbered the number of stone tools found, which is a feature of Andamanese material culture that continued all the way up until colonization. Bone tools, mostly arrowheads, are also found, as well as a small number of flaked stone blades, which were probably used for shaving (for which the Andamanese continued to use very similar stone blades into the colonial era).

Bones are abundant in Andamanese shell middens, predominantly those belonging to pigs, but there are also frequently remains of rodents and varanid lizards, as well as a couple of surprises. Possible single-item finds include the jawbone of a dog (dogs were not found in the Andamans prior to British colonization in the 19th century) and some fingerbones that may have belonged to a monkey.

Pottery is also well-represented in the archaeological record of the Andamans, being found all the way down to the basal layer of the Chauldari midden. The potsherds found in Chauldari and similar middens appear continuous with the Andamanese pottery tradition documented in historical times; however, the pottery found in the basal layer at Chauldari is of significantly finer manufacture than that found in later layers, suggesting a deterioration in pottery-making skills over time. Cooper (2002) reports that petrological analysis of more recent potsherds shows the use of poorer-quality clays that underwent less preparatory refining to remove non-clay materials. Given the abundance of readily available sources of good-quality clay in the modern Andamans, this was probably not the result of resource scarcity or anything like that. Cooper chalks it up to “indifference.” Weird.

We could continue on about these findings ad nauseum. But if you’re an avid student of Southeast Asian archaeology (which I know everyone here is. Otherwise why the hell would you be reading this?), you will have already noticed a few things mentioned in this section that are immediately relevant to the thesis of Andamanese isolation.

Pigs? Pottery? Outriggers?

Recall the title of this piece. I know I’ve really thoroughly confused the issue with thousands of words on the Andamanese people, their culture, and the archaeology of the islands, but remember that this is at heart an interrogation of the idea that the Andamanese have been, in various senses, isolated from the broader world around them for however long. Herein lies the point:

Andamanese material culture doesn’t show, and for at least 2,300 years hasn’t shown, the characteristics of a material culture that’s been isolated from the rest of humanity for tens of thousands of years! If these people were an undisturbed Middle Paleolithic throwback, they’d be going around using five-kilogram handaxes and boiling their food with rocks and leaves. Instead, they use technologies of much more recent invention, from the prosaic to the very specific.

The pottery and microlithic stone tools Cooper found at Chauldari and other sites are characteristic of the Upper (late) Paleolithic, with both generally appearing later than 40,000 years ago in Eurasia. The presence of these technologies in the Andamans is evidence against the strictest possible interpretation of the Andamanese isolation hypothesis. They’re proof that, at least at some point more recent than 60,000 years ago, there was interaction between the Andamans and mainland Asia.

And then there are the more specific characteristics. Take, for example, the presence of pigs in the Andamans, from the earliest layers of the Chauldari midden to the modern day. The Andamanese wild boar is the only mammal larger than a cat found on the islands. At first glance, this appears suspicious. This is the Andaman Islands, after all. Roughly half of the mammal species found there are endemic, found nowhere else on the planet, and that’s because it’s been cut off from the Asian mainland since basically forever. Why, out of all the possible large mammals of Asia that could have made their way across the water, would it be pigs? Why not monkeys? Why not jackals? Why not tigers?

The obvious answer is that they didn’t make their own way across the water. Instead, they were brought, introduced by humans as a domesticated or semi-domesticated population that later went feral. This is a hunch, not a definitive statement of fact, but hunches can be tested for their accordance with the available data.

A real smoking gun would be finding that the oldest layers of archaeological sites in the Andamans lack pig remains, which suddenly show up at a later date. No dice, unfortunately. It’s pigs all the way down. Specifically, Cooper finds pig bones dating to the

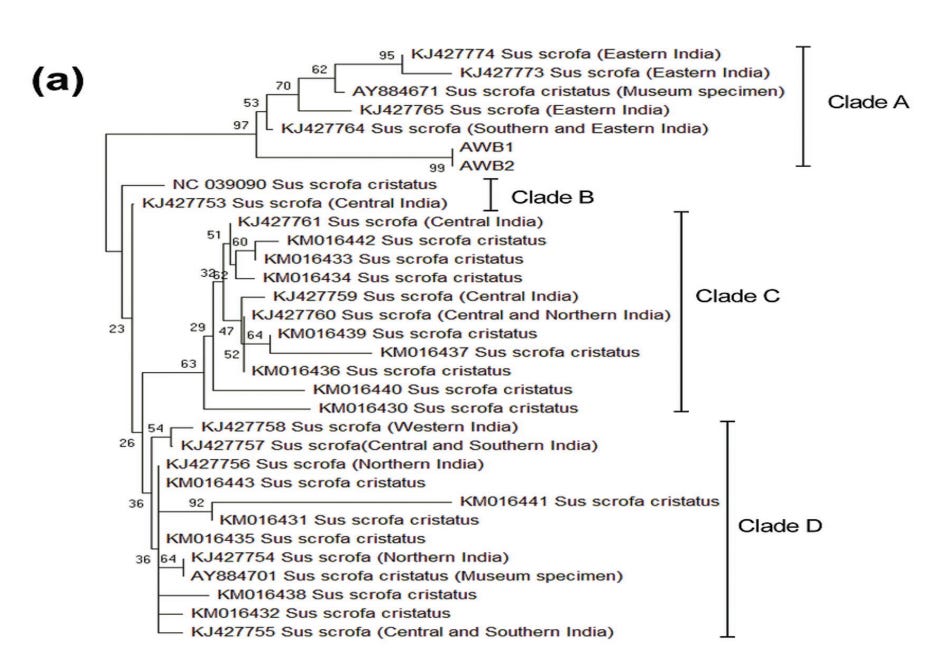

There is, of course, a holier and more coveted form of evidence than mere archaeology. In population history, the gold standard is genetic evidence, broadly meaning when two human populations can be proven to share genetic markers that are indicative of common descent. The “human” part is incidental, actually. You can apply this process to any population of living creatures, provided they share mapped regions of their genomes. But we’re talking about pigs here. Wild animals. Who in their right mind would go through the trouble of mapping and comparing the genomes of pigs?

Oh.

De et al (2022) analyzed the mitochondrial DNA of pig populations across South and Southeast Asia in order to classify the Andamanese wild boar (AWB, in the chart above). They determined it to be of the species Sus scrofa, the Eurasian wild boar, and closely related to Asian populations. In fact, so closely related that it nestles right into their family tree. The Andamanese wild boar is a member of a clade within Asian Sus scrofa, labeled above as “Clade A.” Its closest relatives are a group of fellow boars from southern and eastern India. The authors suggest that a population ancestral to the modern Andamanese wild boar was brought by humans to the islands from eastern India, and, baffling though it may be, I for one can’t argue against that model. Hard to imagine the boars swimming all that way. Actually, I’m imagining that right now. I need to lie down.

Pigs aside, though, the crown jewel, the major counterexample to the isolation hypothesis that can be found in Andamanese material culture, is those canoes.

Outriggers, those sick little floaty things on the side of the boat, are an interesting technology. They’re fantastic for stabilizing “tippy” watercraft: the buoyancy of the wooden float prevents the boat from tipping over too far to one side, while its weight prevents it from tipping over to the other. They’re believed to have originally evolved from the double-hulled catamaran and related boat designs, which are in turn an elaborated version of the humble wooden raft.

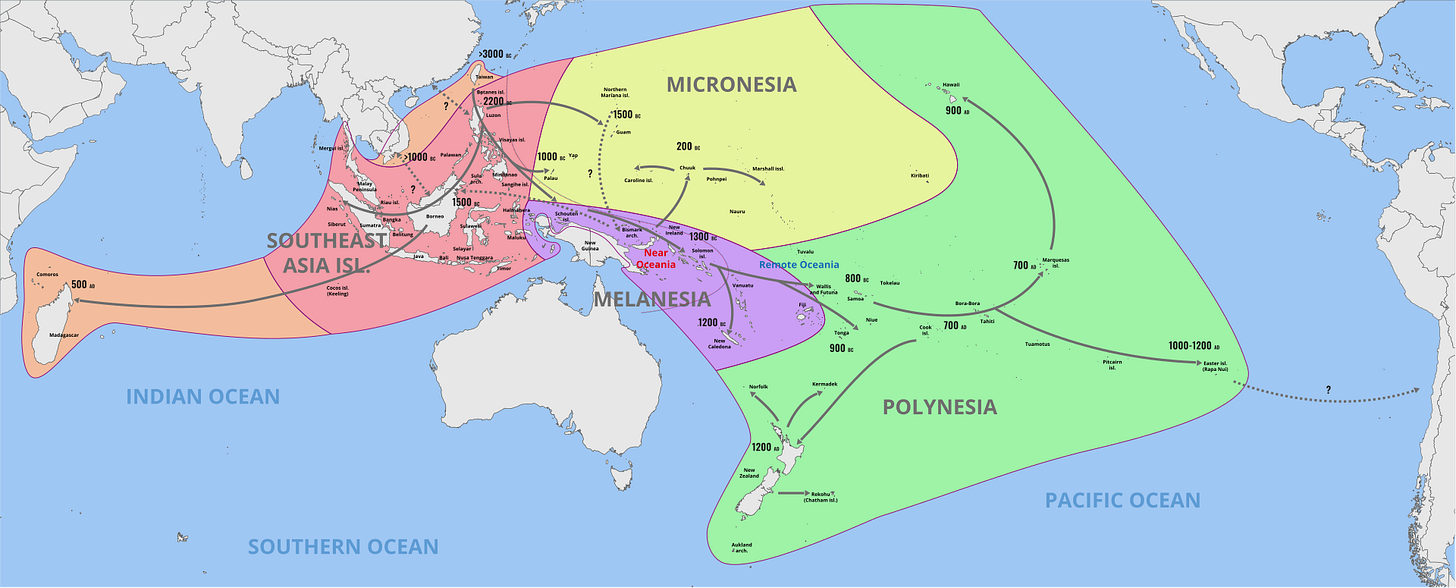

Uniquely, outriggers are thought to have been invented only once in all of human history — by the Austronesian-speaking peoples of maritime Southeast Asia, at some point post-dating the migration of early Austronesian speakers out of Taiwan around 5,000 years ago.

In most of Indonesia and the Philippines, the primary means of maritime transport is in double-outrigger canoes, which have floats on either side. But the geographic distribution of single outriggers, which are found to the east and west of the double-outrigger zone as well as in relict areas within it, like the Barrier Islands off Sumatra, attests to their former dominance across Island Southeast Asia. The double-outrigger is a recent innovation, probably spreading within the last 2,000 years and replacing single-outrigger canoes across much of its range.

The Andamanese use a single-outrigger design, despite their location nearest Austronesian-speaking peoples who use double outriggers. This probably indicates that the technology came to the islands earlier than the last 2,000 years, before the spread of double outriggers in Island Southeast Asia. And yes, they were without a doubt introduced from the outside world; there’s no evidence of other watercraft more complex than a basic raft on the islands, and the likelihood that they independently leapfrogged all of that development and got all the way to outriggers on their own is … we’ll call it slim, I guess? (It’s zero).

In all cases of outrigger adoption, the group adopting the technology has been in sustained contact with speakers of Austronesian languages. The outrigger canoes of the Aboriginal Australians of Cape York are closely connected, both in terms of their construction and the terms used to refer to their parts, with the canoes of Austronesian speakers from the Papuan Tip area in eastern New Guinea (Wood 2018). The Sri Lankan and, by way of descent from them, the East African variants were most likely spread beginning between 1,000 and 600 BCE by traders from Indonesia, participating in the same sprawling regional network that brought the speakers of Austronesian Malagasy to Madagascar (Mahdi 1999b).

The Andamanese almost certainly belong to this set of non-Austronesian adopters of outrigger technology. But this presents an issue, in the context of the isolation hypothesis. While they appear simple on the face of things, outriggers aren’t the kind of technology that appears to spread via simple imitation; the methods of construction are too complex, the principles of operation too abstract. Someone has to teach you how to build one. And someone, probably over 2,000 years ago, taught the Andamanese.

We could leave the issue here, satisfied that we’ve proven yet another avenue by which the Andamanese weren’t isolated from the outside world. And I’m tempted to do so. But Another nail in the coffin of the isolation hypothesis doesn’t really do it for me anymore, though. I’m left with questions, and questions demand answers.

Who taught the Andamanese how to build outrigger canoes?

Some have argued that the lashed peg attachments of the Sentinelese canoes are morphologically similar to Nicobarese ones. But the Nicobarese use only two booms to attach their outriggers, whereas the Sentinelese use many, and other Andamanese groups use different attachment methods. So do we go through all of the Andamanese boat-building traditions and compare them to all of the nearby traditions of Southeast Asia, and probably also India for good measure? That sounds like it would take a while, and it would be a very imperfect approach to the issue. Technologies change over time as people within a society innovate on previous designs, and this is well-documented in cases of outrigger design around the world. Ultimately, this is probably not a question that can be solved by comparing boat-building methods.

We’re going to have to go a little deeper than that.

Layer -2: Andamanese languages

So the archaeological and material record of the Andamans clearly suggests sustained contact with the outside world at a fairly recent point in the past couple thousand years, and probably a couple more points in addition to that. This period, or periods, of contact led to the introduction of pigs, pottery, and outrigger canoes. It’s also possible that they were the motivation behind a change in subsistence patterns, with the inhabitants of the Andamans becoming more oriented towards marine resources for their subsistence. This is attested to by the sudden appearance of shell middens around 2,300 years ago.

But beyond that, the archaeological record sort of runs out of utility. We don’t know where these technologies came from. We don’t know which mainland culture or cultures brought them over. And we’re certainly no closer to answering our burning questions about the initial peopling of the Andaman Islands — where, how, who, when, when, etc.

Here, we can resort to the second of the three major methodologies of population history. When conclusive evidence fails to turn up in the archaeological record, oftentimes we find that languages preserve evidence better. My favorite go-to for this is the spread of the Indo-European language family — in combination with archaeological and genetic evidence, the distribution of Indo-European languages is a key backbone of the Kurgan hypothesis, which been very informative for our models of prehistory in Bronze Age Eurasia.

Unfortunately for our purposes, the Andamanese languages are as singular and distinct as the Andamanese people — which means you need to put a little hard work in to make them talk to you.

There are two families of Andamanese languages, corresponding with the broad ethnolinguistic groupings introduced in a previous section: the northern Great Andamanese family and the southern Ongan family. The Great Andamanese languages are a dialect continuum, with adjacent languages being basically mutually intelligible and more distantly separated ones not. The Ongan languages have more of a traditional family tree structure, with two sharply distinct members: Onge, spoken on Little Andaman, and Jarawa, spoken on South Andaman.

Often, the clearest and most compelling evidence for a connection between two populations in prehistory is what’s called a genetic relationship between their respective languages. This is when you demonstrate, using principles of historical linguistics, that both languages are descendants of a single ancestral “proto-language;” that their relationship — and presumably that of the societies which speak them — is one of common descent.

In the case of the Andamans, the isolation hypothesis generally assumes a relationship of common descent. A group of people entered the Andamans way back in -1,000,000,000 BCE, probably a small group, probably speaking only a single language or set of related languages among them. In the millennia since, that language has diverged into the big language families we see in the Andamans today. Alternatively, if the founding population of the Andamans spoke multiple unrelated languages, then probably all but one were eventually driven extinct by the chaotic competition of violent hunter-gatherer groups over 60,000 years of conflict and change. They’re not very big islands; there isn’t really anywhere to run.

So hypothetically, it should be a pretty simple task to compare the two language families of the Andamans, find some evidence for a relationship, and posit that they’re related. You would think! So far, though, no convincing evidence has yet been put forward for a genetic relationship (i.e. a relationship of common descent from a single ancestral “proto-language”) between the Ongan and Great Andamanese families.

What do I mean when I say “no convincing evidence,” though? Basically, the fundamental assumption of historical linguistics is that languages’ sound systems change over time in a regular and exceptionless fashion. At some point in the development of English, for example, English people stopped pronouncing r’s at the ends of words, in what’s called the coda position. There were no exceptions to this rule; there isn’t a single word that escaped the change. For literally every Early Modern English word that had a coda r, there’s a corresponding English English word without it.

If two languages are related, then — descended from a single common ancestral language, remember — we expect to see that 1) they each retain a set of words traceable back to that ancestral language, and 2) each word can be derived from its corresponding ancestral form via a set of sound changes, which are specific to each descendant language but are applied without exception across the entire lexicon. Historical linguists use a method based on these assumptions, called the comparative method, to classify languages into sets of languages which all derive from a single common ancestor, called language families, and reconstruct the sound system and lexicon of that common ancestor. The basic process is:

Pick through the lexicons of the languages under consideration to find words with the same or similar meanings and a similar segmental structure.

Record correspondences between the sound segments of each sound.

If all of the correspondences in a given pair are systematic (appearing a number of times in the dataset, without exceptions), then congratulations! Those words are confirmed cognates. Once you’ve repeated these steps often enough and have a large set of confirmed cognates, you can move on to reconstructing the sound system and lexicon of the proto-language whose hypothetical existence you’ve just demonstrated.

So if we look at all the words that end with an r in American, Scottish, and Irish varieties of English, and compare those to their counterparts in English English, we’ll find a uniform correspondence of r:ø in the coda position. No exceptions. Congratulations, we’ve just proven that the varieties of English are related to one another (this was a serious point of contention up until now).

The problem with the Andamanese languages is that no one has been able to find a set of cognates that can be connected with one another via these consistent sound correspondences. Hell, actually, the problem is a step lower than that: the lexicons of the Ongan and Great Andamanese families are so distinct from one another that no one has even assembled a significant list of lookalike words. Abbi & Kumar (2011) found 6 words in Aka-Bea and Önge-Jarawa that shared sequences of 2 or more similar segments, out of the 100-word LWT basic vocabulary list. Out of the 40-word ASJP basic vocabulary list, the number was 7 (one of which had to be thrown out). Abbi (2009) concludes that, lexically and grammatically, the two families are very different from one another.

No other serious exploration of the possibility of grouping the Andamanese languages together genetically has been made, beyond passing observations about similarities in their personal pronouns. They are simply too distinct.

This is a problem for the isolation hypothesis, but not an insurmountable one. Most historical linguists believe that constant changes accruing in all subsystems of two related languages can eventually obliterate all evidence of them ever having been related. The general timeframe given, beyond which languages can’t be convincingly demonstrated as related, is around 10,000-12,000 years or so. I have my own personal disagreements with this, but it’s a well-founded argument, as that’s the probable age of the generally accepted “oldest language family,” the Afroasiatic languages. Consistent with the isolation hypothesis would be a scenario in which a group of original Andamanese people, speaking a single Proto-Andamanese language, entered the Andamans, settled on different parts of the islands, and just never interacted with each other for a couple tens of thousands of years. The “never interacted” bit is important, since any two languages in contact usually swap at least a word or two per century or something like that, and there’s no evidence of that going on between Great Andamanese and Ongan. So, not a super plausible scenario, but an acceptable one.

Now, if I were really interested in roundly tearing apart the isolation hypothesis from a genetic comparison angle, though, I would probably not focus on comparing the Andamanese languages with each other. Instead, I’d compare each one individually with other language families from mainland Asia and the rest of the world. If a convincing genetic relationship could be demonstrated between, say, Great Andamanese and the Nihali language isolate of India, creating a family that excludes Ongan, that would be good evidence for a significant exchange of populations between the mainland and the Andamans at some date more recent than the original settlement.

There have been a couple of attempts at this. Joseph Greenberg, a linguist who loved using terrible methodologies to arrive at basically correct answers, included the Great Andamanese languages in his “Indo-Pacific” macrofamily, which lumped them in with the 60-something individual language families of the island of New Guinea together with the extinct and poorly-attested Aboriginal languages of Tasmania. More recently, Blevins (2007) proposed an “Austronesian-Ongan” family, which firmly excluded the Great Andamanese languages. Both of these hypotheses have been roundly criticized by more or less every linguist who’s actually read through them, and I for one agree. Greenberg’s methodology of mass comparison is not a good tool for establishing genetic relationships between a large set of languages, as it fails to distinguish between loanwords, chance lookalikes, and actual cognates. The only time I’ve seen it come in useful is in providing a very basic overview of the relationships between closely related language varieties (when no real historical work is available). Blevins’ comparisons between Austronesian and Ongan, on the other hand, mostly follow the kind of regular correspondences you’re supposed to cleave to in genetic comparison, but the semantics of her supposed “cognates” are insane. Very few of them are actual 1:1 comparisons; for the majority of them, you’ll see a word for “tail” compared with one for “hair,” or “fruit” with “flower,” or “new” with “good” (and those were just three random ones I picked out off of page 169). When your application of the comparative method permits the kind of semantic flexibility that lets you compare “I” with “them” (true story), I feel justified in throwing your whole set of correspondences in the trash. They are completely without value.

So we can admit defeat. The genetic comparison road is a bust. But don’t let it dishearten you (why would you let it dishearten you???). Because we can engage in other types of lexical comparison, ones that don’t entail the positing of a genetic relationship.

Often, languages borrow words from one another — when in sustained close contact with another language, or when one language’s speakers introduce a new concept or technology to the other’s, or often just for the hell of it. Digging through these borrowed terms and figuring out who borrowed what from whom and when is loanword analysis, and it can be a very useful tool for uncovering the mechanics of inter-population interactions in prehistory.

In the case of the Andamans, we have a solid basis for targeted loanword analysis: we know that a number of things, including pottery, pigs, and outrigger-equipped canoes, were spread to the Andamanese via interactions with the outside world. If we can figure out where the Andamanese got their words for these concepts, that gives us a promising direction for even more loanword analysis, geared toward determining whether the interaction went further than just a utilitarian exchange of technologies. Loanword analysis is kind of like site excavation in archaeology. You keep digging and make sure to label your layers as you go.

The Önge, Jarawa, and selected Great Andamanese terms for introduced technologies follow (Aka-Bea and Aka-Kol from Portman 1898, some Önge from Portman 1899, Önge and Jarawa from Blevins 2007, and Present-Day Great Andamanese from the Present-Day Great Andamanese database):

“Pig” - Önge kui ‘pig, animal,’ Jarawa hoi ‘id.;’ Aka-Bea reg ‘pig,’ Aka-Kol reak ‘id.,’ Present-Day Great Andamanese ra ‘id.’

“Pot” - Önge búchu ‘pot;’ Aka-Bea búj ‘pot;’ Aka-Kol péch ‘id.,’ Present-Day Great Andamanese pʰɛc ‘a kind of pot for making food,’ fɛc ‘vessel’

“Outrigger canoe” - Aka-Bea chárigma ‘canoe (with outrigger),’ Aka-Kol ch’rok ‘id.,’ Present-Day Great Andamanese cɔrɔkʰ ‘horizontal bars of outrigger’

“Canoe” - Önge taŋe, daŋe ‘log, tree trunk, stem; canoe,’ Jarawa taŋ, daŋ ‘id.;’ Aka-Bea róko ‘id.,’ Aka-Kol rāū ‘id.,’ Present-Day Great Andamanese roːɔ ‘canoe; dongi, a kind of boat’

And behold, the data suggests an analysisǃ What’s initially clear here, without even looking at comparative data, is that these technologies were almost certainly introduced to Great Andamanese speakers first, and only later spread to Ongan speakers. The Önge words for ‘canoe’ and ‘pig,’ which both date back to Proto-Ongan (Blevins 2007), appear to just be repurposed words for ‘tree’ and ‘animal’ respectively, and the Önge word for ‘pot’ is borrowed from the Great Andamanese Aka-Bea or Akar-Bale languages (which share a unique sound change of Proto-GA *pʰ > b). I haven’t been able to find any Ongan words for the Andamanese outrigger canoe.

The Great Andamanese terms for these four words are all cognate with one another, and appear to date all the way back to their common ancestor Proto-Great Andamanese. Since I’ve done some of my own (yet to see the light of day, unless you were at the ULAB conference in April) comparative work on Great Andamanese, I thought I’d include my reconstructions of these terms below:

“Pig” - PGA *rakʰ

“Pot” - PGA *pʰac

“Outrigger canoe” - PGA *carikʰ(ma)

“Canoe” - PGA *rokɔ

Least interestingly, one of these terms is of ultimate Austronesian etymology, and it’s the one that’s associated with a uniquely Austronesian invention: the outrigger. The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary of Blust & Trussel lists the reconstructed form *saRman ‘outrigger float,’ which is segmentally quite similar to PGA *carikʰ(ma) (the Andamanese languages lack fricative phonemes, and almost always borrow other languages’ s as a palatal affricate /c/). Wood (2018) argues for a reconstruction of this form as *saRiman in the Austronesian Papuan Tip languages; if the *i is a retention from Proto-Austronesian, it would put the comparison with PGA *carikʰma on firmer ground. The immediate donor language for this form is not obvious, but was probably a now-unknown early Western Malayo-Polynesian language (perhaps the same non-Malay WMP language that loaned sailing terminology into Dravidian; see Mahdi 1999b).

The other three terms are of Austroasiatic/Munda origin (comparisons via the Mon-Khmer Comparative Dictionary and Munda Comparative Dictionary).

PGA *rakʰ ‘pig’ : Proto-Mon-Khmer *liik ‘pig’

PGA *pʰac ‘pot’ : Proto-Mon-Khmer *buəc ‘a kind of small vessel’

PGA *rokɔ ‘canoe’ : Koda lauka ‘boat,’ Mundari lauka ‘id.,’ Mahali leuka ‘id.,’ Santali lɨukɨ ‘id.;’ compare Proto-Mon-Khmer *ɗuk ‘boat’

There are a number of other pretty convincing lookalike lexemes shared between Munda languages and Great Andamanese ones, too! For an incomplete and vaguely slapdash list:

Aka-Bea bāūrōīn ‘mountain,’ Aka-Kol búrin ‘id.,’ Present-Day Great Andamanese buruin, buːruɲ ‘id.’ : Bodo-Gadaba buroŋ ‘hill, mountain,’ Mundari buru ‘id.,’ Sora bəruː-n ‘hill, mountain, forest’

Aka-Bea rāīch ‘to bail water,’ Aka-Kol rāīch ‘id.,’ : Mundari arɛˀɟ ‘to bail water,’ Bodo-Gadaba aǰ ‘id.,’ Sora uɟ- ‘to sprinkle, bail out’

Aka-Bea láka ‘digging stick,’ : Mundari laʔ ‘to pare wood with an axe, or the ground with a hoe,’ Sora loː ‘to hoe,’ Juang la ‘to dig’

Aka-Kol kók ‘bow,’ : Mundari aʔ ‘bow,’ Kharia kaʔ ‘id.,’ Juang kakag, kakkad, kakkar ‘id.’

Aka-Kol póng ‘hole,’ Present-Day Great Andamanese pʰoŋ ‘id.,’ : Gtaʔ ara=poŋ ‘slant of a hole,’ Mundari baŋ-boŋ ‘several holes which go through,’ Birhor phōnka ‘a hole, to open out,’ Sora ə-piŋ ‘hole’

Wait … what?

What the hell?

The Munda languages are a branch of the Austroasiatic family, which is widely considered the oldest and most diverse living language family of Southeast Asia. And they’re a real outlier among them. Geographically, the Munda group is found exclusively in certain pockets of eastern India, though it’s believed to have been more widespread previously. Typologically, it presents a profile (argument-indexing, noun incorporation, and huge & complex inflected verbs) that’s quite distinct from the other languages of the Austroasiatic family, which has caused some to believe that it might be the earliest-branching member. I say “some” as if it wasn’t almost universal consensus as recently as 20 years ago. Nowadays, there’s a larger contingent of specialists who accept that the unique typological features of the Munda languages are probably an independent development, and that it branched off around the same time as all of the other Austroasiatic branches.

That being said: Munda languages aren’t spoken anywhere near the Andaman Islands. All modern Munda language communities are located in upland regions of eastern India, often quite isolated and rugged ones:

A trip from the Great Andamanese-speaking area to the Munda-speaking area isn’t a simple one-leg jaunt. There’s a considerable distance of water to cover, combined with an inland trek of, at the very least, 100 kilometers. It’s believed that Munda-speaking communities were formerly more widespread in eastern India, before the expansion of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers into the area, but there’s no evidence that they engaged in the sort of long-distance voyaging that would be necessary to reach the Andamans.

Or is there?

Traditionally, the original point of dispersal of the Austroasiatic languages is believed to have been in Southeast Asia or southern China (there are some “out of India” truthers left, but this post is way too long and I’m way too tired to deal with all that). On the basis of reconstructed vocabulary, it’s believed that the speakers of Proto-Austroasiatic were inland Neolithic cereal agriculturalists adapted to a riverine lifestyle (Sidwell & Blench 2011). The general view of the family’s early history is centered on a rapid dispersal of the original speech community along the major rivers of Southeast Asia — the more eastern branches, like Pearic and Khmer, spread down the Mekong, the more western branches, like Mon, spread down the Irrawaddy, and the Munda branch spread down the Brahmaputra.

However, more recently a different proposal has been gaining traction among Austroasiatic specialists: the “Munda Maritime Hypothesis” of Rau & Sidwell (2019). Considering the huge suite of problems associated with a land-based migration of Munda into India (the lack of Munda/Para-Munda languages in the Brahmaputra valley and Indo-Gangetic Plain, the lack of evidence of there ever having been Munda languages in the Brahmaputra valley and Indo-Gangetic Plain, the Munda center of diversity lying to the south instead of the northeast), the authors propose a Proto-Munda speech community located in the Mahanadi Delta of coastal eastern India — which arrived there from Southeast Asia by sea between 4,000 and 3,500 years ago.

This model agrees much better with our linguistic data! Or maybe “agrees” isn’t a strong enough word. Better to say that it fits like a key in a lock. It fits with the geography. It fits with the timeline. It fits precisely with the presence of Munda loanwords relating to maritime concepts (“boat,” “bail water,”) in Great Andamanese. Call me convinced: by all appearances, the ancestors of the Proto-Great Andamanese speech community were participating in the same maritime network that connected Austroasiatic Pre-Munda speakers in Southeast Asia with the Mahanadi Delta. And the pigs can inform us of the direction the contact was coming from: based on the genetic affinity of the introduced Andamanese wild boar with populations from eastern India, these would have been Munda-speaking seafarers from eastern India, post-maritime migration.

So now the evidence has pointed us to a set of conclusions. From the archaeological data, we’ve developed a hypothesis around a contact episode that occurred between the Andamanese and people from the Asian mainland no less than 2,300 years ago — probably between the Andamans and coastal eastern India. This contact episode would have mediated the spread of pottery, pigs, and possibly outrigger canoes into the islands, and triggered a shift in subsistence strategies towards a more marine-oriented economy. From the lexical data, we’ve gotten some additional information telling us that speakers of Proto-Great Andamanese, or a language ancestral to it, engaged in contact with seafaring speakers of Munda/Pre-Munda languages — contact which the speakers of Ongan languages did not participate in. The fact that the Great Andamanese words for the technologies brought to the Andamans from the mainland are of ultimate Austroasiatic etymology indicates that these contact episodes were one and the same.

But here is where the utility of the linguistic record runs out. We’ve wrung it, in combination with the archaeological record, for just about every drop of information it can give us. And yet, we’re still left with questions. What were the dynamics of contact between Great Andamanese and Munda speakers during this episode of interaction? Why do Ongan speakers seem to have not participated in it? How long did the period of contact last?

If we want further answers, we need to look to other methodologies. Fortunately, there’s at least tool remaining in the population history toolbox, and in many ways it’s the most powerful one for looking at deep prehistory. Things the archaeological and linguistic records are too shallow or incomplete to meaningfully preserve. That’s right, ladies and gentlemen, bust out your calipers and consult your skull collection: it’s time to talk genetics.

Layer -3: Andamanese genetics

So far, what I’ve argued for in the previous two sections is a model of population movement. At some point, the speakers of Great Andamanese languages appear to have been in contact with a mainland Asian population, which spoke Munda/Para-Munda languages, and possibly another that spoke Austronesian languages. These populations introduced a set of technologies to the Great Andamanese, which potentially led to a change in the entire subsistence economy of the islands.

This model is a radical departure from the competing isolation model that’s enjoyed a sort of tepid, uncritical mainstream acceptance in the past. And new, substantially different models require bucketloads of evidence. Now that we’ve exhausted our evidence from archaeology, material culture, and linguistics, it’s time to turn to the last major source of data we have to rely on: the genetic record.

There are many different types of contact scenario, all of which leave different evidence in the archaeological, linguistic, and genetic records. Sometimes two groups will exchange material goods without talking to or ever even seeing each other, in what’s called a “silent trade” relationship. One group comes, leaves some goods where the other group will find it. The other group comes, takes what they want and leaves behind some goods of their own. Some have argued for the existence of silent trade relationships in the Andamans prior to colonization, but that’s clearly not what’s going on here.

Because the contact between Great Andamanese and Munda speakers was anything but silent. They didn’t just exchange goods, they exchanged technologies, they exchanged words referring to technologies. By the looks of things, they also exchanged words that weren’t really related to technology at all. There are a couple of situations this could reflect. Maybe it was a strictly trade-based relationship, and the extra words spread into Great Andamanese are just nice little extras or chance resemblance. Or maybe there was more substantial contact — cohabitation, even intermarriage.

The genetic record will help us determine what kind of contact went down. But, if you’re unfamiliar with how genetics are used in population history, here’s a refresher:

Mutations occur in the human genome pretty regularly, and once they crop up they are a permanent part of the genome of the individual they occur in as well as the genomes of all of their descendants. By analyzing the non-coding segments of many individuals’ genomes from many populations for mutations, one can pinpoint certain combinations of mutations that serve as clear markers of descent — called “haplogroups.” By analyzing the diversity of these haplogroups within an entire population, one can draw connections between populations exhibiting the same or similar haplogroups, which must necessarily be related (in a very literal, biological sense).

Say you have Population 1, which exhibits a 34.6% rate of Haplogroup ?1a1b, and Population 2, which exhibits a 51.1% rate of Haplogroup ?1a1b (that’s just what the naming conventions are like, I’m so sorry). If Haplogroup ?1a1b has been determined to have a ~4,000 year coalescence time (roughly speaking, the time at which it emerged), we can assume that, around 4,000 years ago, there existed a population that many of the individuals in Population 1 and Population 2 could trace their ancestry back to. Quite a few, judging by the high rates at which ?1a1b is found in both populations.

While haplogroups within autosomal DNA (the DNA found in the 44 non-sex chromosomes of the human genome) can be analyzed, population genetics tends to focus mainly on mutations in uniparental genetic markers — those found in the Y-chromosomal or mitochondrial DNA. These are passed from parent to offspring without undergoing recombination, with Y-chromosomal DNA passed from father to son and mitochondrial DNA passed from mother to child.

The virtue of genetic analysis is that, unlike material culture and comparative linguistics, DNA doesn’t lie. There’s no doubting the genetic interrelatedness of Populations 1 and 2 at the time depth specified in the previous example; the presence of ?1a1b attests to it. Of course there are, as with any method of analysis, a number of potential pitfalls — small sample sizes skewing results, small population sizes causing noise-amplifying genetic drift, coalescence times with extremely wide error bars, etc. But for the most part, genetic evidence is considered the most ironclad evidence for population movements in prehistory.

With that being said: what does the genetic record say about the Andaman Islanders?

The mitochondrial DNA record is the clearest. The first major mitochondrial DNA study of the Andamanese (Thangaraj et al 2005) sampled the Great Andamanese of Strait Island and found 2 specific haplogroups among them, M31 and M32. The authors checked these sequences against a dataset of 6,500 mtDNA sequences from mainland India, none of which was a more specific match than the M haplogroup (one of the ‘big two’ mtDNA haplogroups outside of Africa, estimated to have arisen around 70,000 years ago, right after the migration of humans into Eurasia). You really couldn’t ask for clearer results; the authors concluded that the most likely scenario of human colonization of the Andamans was a single, very early migration, shortly after the first anatomically modern Homo sapiens left Africa.

As is often the case, the very first conclusion drawn on the issue ended up becoming the standard line, and the theory of a Middle Paleolithic origin of the Andamanese remains current among journalists and, more worryingly, some actual academics studying the prehistory of the Andamans. These words will sound harsh, even bitter, but please understand my position:

The very next year, Palanichamy et al (2006) reported two individuals outside of the Andamans that exhibited a subclade of the Andaman-specific M31 mtDNA haplogroup, termed M31b in opposition to the Andamanese M31a. The presence of M31b outside of the Andamans strongly suggested that settlement here couldn’t have been as early as was suggested in Thangaraj et al (2005). No prizes for guessing where these M31b-having individuals were from, by the way (it’s India, it’s northeast India, of course it is).

Thangaraj et al (2006) hit back at this, arguing that M31a and M31b are distinguished from one another by a large number of mutations and, as such, finding examples of M31b in India shouldn’t invalidate the early settlement theory.

But the studies finding evidence of M31 on the Asian mainland just kept on coming. Between 2006 and 2009, 4 more studies reported new examples of the haplogroup in India, Southeast Asia, Nepal, and China. This research is all beautifully summarized by Wang et al (2011), including how it complicates the situation for the early settlement theory. Here is their revised M31 family tree:

Definitely more interesting than what we got out of the original study in Thangaraj et al (2005)! The authors report a coalescence time for M31a (including the Andamanese-specific M31a1 lineage and its closest then-known mainland relative, M31a2) of 19.82±10.01 kya (thousand years ago). Simply put, the earliest possible time M31a1 could have been introduced to the Andamans is somewhere more recent than the period between 30,000 and 10,000 years ago — more or less conclusively obliterating the early settlement theory.

Barik et al (2008) summarize the evidence up to that point pretty well, asserting that a “very recent” — i.e. less than 10,000 years ago — settlement of the Andamans is supported by the genetic evidence, citing newly-calculated coalescence times of 7±5 kya for M31a1 and 3±2 kya for M32a (which, interestingly, is a clade that excludes one Great Andamanese M32 lineage found in the study. The actual coalescence time of all Andamanese M32 lineages in the study would be greater than 3±2 kya).

The most recent studies of Andamanese mtDNA are largely in agreement with respect to the recent (Holocene-era) coalescence times of M32 and M31a1. Sitalaximi et al (2023) report coalescence times of 9700±4300 years for Andamanese M32 and ~1500 years for Andamanese M31 lineages. The very early settlement hypothesis is dead! Long live the very recent one!

And here I’d like to make a point of order, before we move on to the literature on Andamanese Y-DNA markers. The abundant evidence of mtDNA haplogroup M31 in mainland India is not matched by any corresponding examples of M32. While M31 survived and diversified in mainland Asia (albeit probably among relatively small populations, judging by its rarity today), M32 is completely gone everywhere except in the Andamans.

It looks like, although M32 and M31 are both found in the Andamanese of the modern day, they were historically found in two separate populations in mainland Asia. The population that carried M32* left no descendants on the mainland, with their unique mtDNA signature surviving only in the Andamanese. The population that carried M31* appears to have been more successful. Their descendants are found both on the mainland and in the Andamans. At some point, groups descending from the original M32* and M31* populations merged into a single population: we could call them the Ancestral Andamanese population, for shorthand. This merging took place sometime in the last 10,000 years or so, and probably more recently than that, judging by the respective coalescence times of the M31a1 and M32 haplogroups. That’s the main takeaway I want to underscore here, the main story the mtDNA record is telling us.

The Y-DNA record is just as interesting, if maybe not so thoroughly researched. If I’m being honest, it’s actually full of some serious issues, mostly deriving from faulty assumptions about Andamanese prehistory. First and foremost, Y-chromosomal DNA sampled from Önge and Jarawa men tends to be described in the literature as “Andamanese” DNA, despite those two tribes representing only a small portion of the up to fifteen distinct ethnolinguistic groups of the pre-colonial Andamans. Second and secondmost, Y-chromosomal DNA sampled from Great Andamanese-speaking men tends to be ignored, handwaved, or not even consulted at all. This is on the general principle that Great Andamanese Y-chromosomal DNA cannot be trusted to present an accurate picture of pre-contact diversity, since the modern-day Great Andamanese people have undergone significant admixture with populations from the mainland during the colonial period and afterward. It’s usually assumed (and not incorrectly) that this admixture was mediated almost entirely by male donors. Don’t think about it too hard.

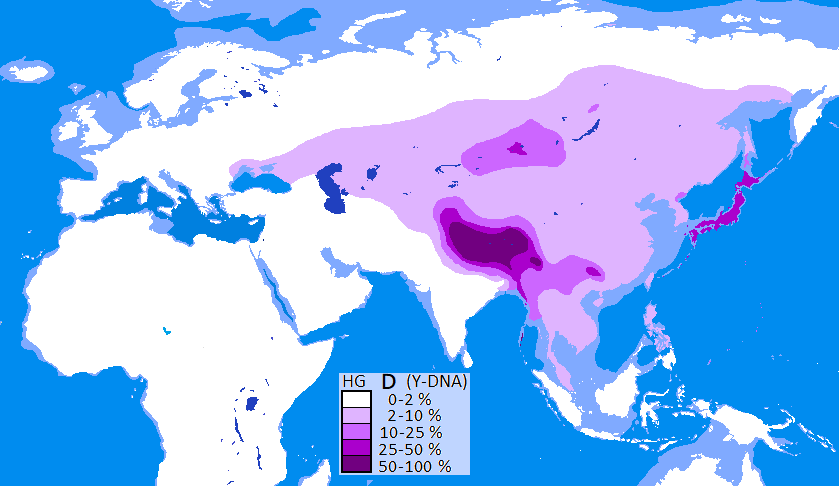

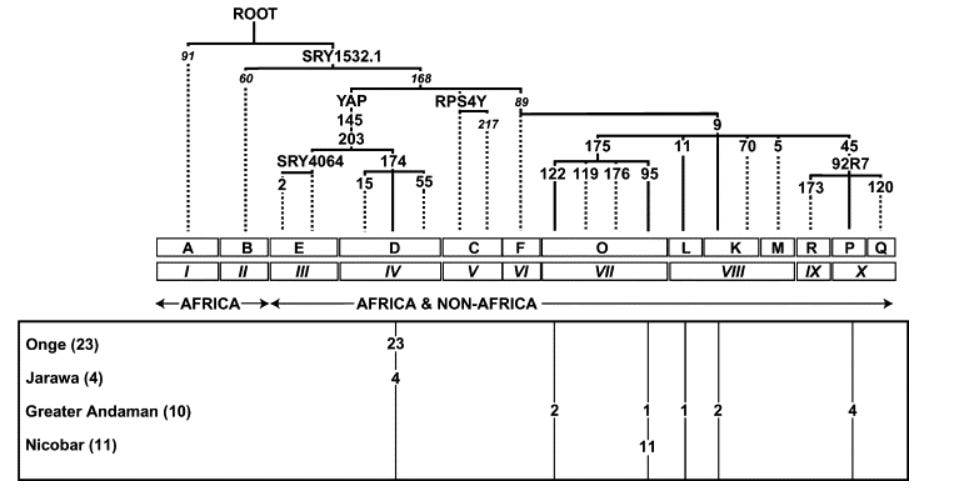

Be that as it may, there are some great studies of Andamanese Y-chromosomal diversity out there, as long as you stick to the “methodology” and “results” sections and don’t ever look at the “discussion” ones. The first study to report data from Andamanese males reported a couple of interesting findings. First, every Önge and Jarawa individual sampled belonged to the Y-DNA haplogroup D, which is found across Asia at generally low rates that spike in the Tibetosphere, Japan, and parts of Central Asia.

The specific variant of Haplogroup D found in the Önge and Jarawa, D1a2b, is most closely related to the D1a2a haplogroup, found at modest rates (~33%) among Japanese people and very high rates (~75-90%) among the indigenous Ainu of Hokkaido and Sakhalin. “Close” is a very relative term here, of course; Mondal et al (2017) estimate the coalescence time of the two lineages at 53±2.7 kya. A very old and deeply branching clade, then. Probably all the presence of D in Önge and Jarawa males tells us is that the male ancestors of these people arrived in the Andamans a very long time ago — long enough for the Y-chromosomal DNA of their nearest relatives to have been replaced ~basically without a trace on the mainland, surviving only in the Japanese archipelago.

More recent studies have yielded similar results: among the Önge and Jarawa, both living individuals and museum specimens (thanks, Britain, you fucking sickos), the exclusive paternal haplogroup is D1a2b. Mondal et al (2017) calculated a coalescence time of 7±2.7 kya for the Andamanese D1a2b variants in their study. That pretty much gives us a floor (4,000-10,000 years ago) and a ceiling (50,000-56,000 years ago) for the entry of males bearing D1a2b into the Andamans. We can use this, in combination with the mtDNA data and the Y-DNA data from Great Andamanese individuals, to inform a model of migration into the Andamans.

Speaking of those Great Andamanese individuals. Interestingly, the original study found no examples of Y-DNA Haplogroup D1a2b among Great Andamanese males. In fact, no subsequent study has found any evidence of this Y-DNA marker outside of Öngan and Jarawa individuals.

As is generally assumed, males of the historically Great Andamanese-speaking population exhibit a diverse set of Y-DNA haplogroups, in stark contrast to the single D1a2b haplogroup found among the Jarawa and Önge. Does the second half of this assumption — that this is the result of recent admixture with males from mainland Asia during the colonial period — bear out?

Of course it doesn’t.

Thangaraj et al (2003) report five distinct Y-DNA haplogroups among the 10 Great Andamanese males sampled in their study:

For those keeping score at home, that’s 2 O-M122, 1 O-M95, 1 L-M11, 2 K-M9, and 4 P-M45 (ew, shorthand notation), for a total sample of 10 extremely genetically diverse Great Andamanese men. The authors have an interesting analysis of this diversity:

“In contrast to the single Y haplogroup observed in the Onge and Jarawa males, the Great Andamanese had five different binary mutation haplotypes, falling into haplogroups O, L, K, and P, among ten men. This suggests admixture with Indian (L-M11 and P-M45) and East Asian (O-M122 and O-M95) male lineages. European Y chromosome lineages, like those related to R-M173 [34], were not observed. These findings reflect the history of the Great Andamanese in colonial times. The tribe was pacified forcibly by the British in the 19th century and coexisted with thousands of male laborers and convicts from the Indian mainland. The few surviving members of the Great Andamanese tribe are now settled in Strait Island in the Andamans and bear little physical resemblance to other Andamanese.”

No further discussion of Great Andamanese Y-DNA diversity is given.

Some aspects of this thought process, I have no problem with. O-M122 (O2, to its friends) is the dominant Y-DNA haplogroup of East Asia. It probably emerged as early as 35,000 years ago somewhere in Southeast Asia, but its distribution nowadays seems to have been mediated by the Holocene-era spread of groups speaking languages of the Trans-Himalayan macrofamily (also called Sino-Tibetan, by those who enjoy being wrong). O-M95 is the defining Y-DNA haplogroup of Nicobarese islanders, the southward neighbors of the Andamanese. L-M11 is widely distributed in India. Considering that these three Y-DNA haplogroups are expressed at high rates by populations that were likely to have contributed convicts to the British penal colony at Port Blair in historic times, it’s reasonable to assume that they’re recent introductions to the Great Andamanese population.

But to paper over this whole genetic diversity with no further comment beyond “admixture,” with not even any mention of the fifth haplogroup uncovered in the study, is just misleading. By omission, it allows the reader to walk away with an inaccurate picture of the analysis recommended by the data. Because the two Y-DNA haplogroups found in the remaining 6 Andamanese males sampled are very poor candidates for recent introduction. Shockingly poor candidates. Let me explain.

K is a very, very widely-distributed haplogroup, like, to the point of ridiculousness (it actually contains within it all of the other Y-DNA haplogroups discussed in this section, including P, Q, R, L, and O). The specific variant of K tested for and found among the Great Andamanese, however, is basal K* — a rare and under-researched clade. It’s been documented to occur at high rates in the “Negrito” groups of the Philippines, a complex of Southeast Asian populations that share some cultural and phenotypic characteristics with the Andamanese (e.g. skin color, hair texture, and a hunter-gatherer mode of subsistence). Aeta males exhibit it at 87-100%, other Negrito groups at 10-25% (Delfin et al 2011). There are also traces of it elsewhere in Southeast Asia, e.g. among eastern Indonesians (20% of a sample of 55) and Melanesians (24% of a sample of 53).

To date, there’s no evidence of K* in South Asia (0% out of a sample of 496) and very little (5% of a sample of 21) in Western Indonesia (Karafet et al 2005; no data on K* in MSEA). Considering this, it’s pretty likely that the examples of it uncovered in Thangaraj et al (2003) are not the result of admixture, but instead bona fide representatives of pre-colonial Great Andamanese Y-chromosomal diversity.

The other major Y haplogroup among the Great Andamanese in the sample, P-M45 (P1), is the ancestor of the extremely widely distributed Q and R Y-DNA haplogroups, which account for the majority of the male populations of Europe and the pre-Columbian Americas, as well as a healthy minority of Asia’s. Significantly rarer, however, is P1(xR,Q) — members of the P1 haplogroup that don’t exhibit the mutations that define R and Q. That’s what’s been tested for in the aforementioned study, and that’s the result that 4 out of 10 Great Andamanese men returned.

But it’s quite uncommon, as Y-DNA haplogroups go. There are groups which exhibit some amount of P1(xR,Q) (also called P1*), but only a certain number, and none at rates as high as the Great Andamanese. It’s found at moderate rates (~25% of males) in some Central Asian populations, and at low rates (0-10% of males) across much of India, peaking at around 15-20% among groups that speak the Austroasiatic Munda languages (remember them?). But these are low frequencies that only rise to moderate in certain isolated populations. It just seems very improbable that the 40% of Great Andamanese men who exhibit P1* can be explained through admixture with a population that exhibits it at a lower rate. A ridiculously lower rate, in the case of most of India outside of the sparsely-developed eastern hills most Munda languages are spoken in, and where the highest rates of P1* are found. And for some reason I doubt a lot of the convicts interned at Port Blair were coming from that area. Does it really seem reasonable, with these kinds of numbers involved, to assume that P1* was spread to the Great Andamanese via admixture? No, not really. To me it kind of just seems like motivated reasoning.

So we can preliminarily, based on just one old 2003 study of the Great Andamanese, file away K* and P1* as the likeliest candidates for indigenous Great Andamanese Y-DNA diversity (by virtue of it having been unlikely or impossible for them to be the product of recent admixture). There have only been a couple subsequent studies of Y-DNA diversity among the Great Andamanese since then, but all of them have basically confirmed the results of Thangaraj et al (2003), with a couple of additions. Moreno-Mayar et al (2018) documented Y-DNA haplogroup P1* in the preserved corpse of an Andamanese man. Sitalaximi, Varghese, & Kashyap (2023) found haplogroups L, R1a, and P* (a sister clade to P1*) in a sample of 13 Great Andamanese men. The former two are almost certainly recent introductions.

So we have a set of 3 probable Y-DNA haplogroups borne by Great Andamanese men in pre-colonial times: K*, P1*, and maybe P*. Unfortunately, there haven’t been any published attempts at calculating things like coalescence times or even identifying closest relatives among the non-Andamanese representatives of these lineages.

But we don’t need coalescence times or closest relatives for one thing to be very clear: the apparent pre-colonial Y-DNA diversity of the Great Andamanese bears no relationship whatsoever to that of the Ongan-speaking Önge and Jarawa. D and K/P are about as far apart on the family tree as two Y-DNA haplogroups can get without going all the way back to Africa. In fact, some population geneticists have argued that their common ancestor would have been found in Africa, prior to the first migration of humans into Eurasia. We’re talking between 70,000 and 100,000 years of accrued mutations separating the two.

There are two language families spoken in the Andaman Islands, which have as yet never been convincingly demonstrated to be related. There are two deeply branching mtDNA haplogroups, which share no common ancestor earlier than 60,000 years ago. And there are two mutually exclusive suites of Y-DNA haplogroups, which correspond unfailingly to the language family of the individual carrying them, and which both have closer relatives distributed across the Asian mainland and beyond.

Despite this, the mainstream conversation around the peopling of the Andamans for many years remained stuck with “did human beings migrate to the Andamans 60,000 years ago or 12,000 years ago?”

But that’s missing the entire pointǃ The problem isn’t with the time depth of the supposed initial migration of humans into the Andamans. The problem is that none of these findings make sense under a model that assumes a single founder population. Why can’t we find any cognates between the two language families, despite the abundant evidence for a recent peopling of the Andamans? Why did M32 die out on the mainland, while M31 survived? How did the entirely unrelated Y-DNA haplogroups P/K and D become the defining genetic signatures of the Great Andamanese and Ongan populations? A single population that exhibits two distinct genetic markers doesn’t just separate into two populations, each of which exhibits only one. There’s just no mechanism by which that kind of sorting can occur.

We’ve clearly been going about this all wrong. The argument shouldn’t be whether the Ancestral Andamanese population arrived in the islands in the Holocene or the Pleistocene. The argument should be whether there even was a single Ancestral Andamanese population in the first place. And if we want to square the evidence from linguistics, genetics, and archaeology … then the correct answer has to be no.

The bottom: A story about the prehistory of the Andaman Islands