1. The Marajóara culture

Take a look at northeastern Brazil, where the Amazon, Xingu, Tapajos, and Tocantins Rivers meet to form the world’s largest delta system. Every second, 224,000 cubic meters of freshwater flow through here to the sea; the runner-up, the Ganges-Brahmaputra system, has a discharge rate of around 44,000 cubic meters, or about 19.6% of the Amazon’s total. In fact, more water flows through the Amazon than the combined total of the 6 next largest river systems.

Here, at the mouth of the world’s largest river, is the world’s largest island built entirely of deposited fluvial sediment. Marajó Island is around 50,000 km² in area, roughly the size of the countries of Costa Rica or Bosnia. Ecologically, it’s divided into two major segments: the southwest, which is heavily forested, and the northeast, which is an open savannah environment with only very sparse tree cover, called the campos by local inhabitants.

The campos are without a doubt an extreme environment, defined by the seasonal floodwaters of the Amazon. During the summer, the prevailing condition is drought, as many rivers dry up entirely and those that don’t have their rate of flow severely reduced. During the winter, the floodwaters rise by around 4 meters, inundating much of the island’s land area. Between those two seasons, the land is some degree of muddy and the rivers are some degree of low.

These conditions are, in a word, hostile. Any environment where water levels annually fluctuate by the height of over two grown men, only to recede to the point of widespread water scarcity within a few months, is going to be challenging for human beings to survive in. It’s probably no surprise that, in the modern day, large parts of the Marajó campos are only seasonally occupied by ranchers and fishermen.

And yet, a casual observer out on the campos might notice something unusual about the local topography. The land is low and flat, yes, and the vast majority of it ends up inundated when the local floodwaters rise. But there do exist parts of Marajó that the winter floods never reach. Small, localized promontories, rising between 4 and 10 meters above the height of the surrounding alluvial plain. Depending on the time of year, you might instinctively refer to them as hills or islands, defined by their elevation.

Their regular shape belies this impression: they are generally circular or oval, at odds with the natural lay of the land. On Marajó, Portuguese speakers refer to them as tesos -- generally translated in English-language literature as mounds.

If you’re some kind of sicko who enjoys studying landscapes and topography, this might immediately strike you as odd. Rivers normally deposit their sediments pretty evenly across their respective floodplains, creating the kind of flat landscape you see across most of the Marajó campos. Promontories like the Marajó tesos tend to find themselves eaten away by erosion over the years. And indeed, it’s obvious that many tesos have been eroded by the seasonal floods over the past several hundred years.

Simply put, these clearly aren’t natural landforms. The Marajó tesos are artificial mounds, built up not by the Amazon but by human hands. This was confirmed by early archaeological surveys in the late 19th century. One of these preliminary works gives a particularly evocative description of the sheer density of pottery sherds at one site:

“The best known mound is situated by the side of lake Arary, and in the winter becomes transformed into an island called the Island of Pacoval. In shape it is nearly oval, having a length of one hundred and fifty meters, a breadth of seventy meters, and a height of five meters above the water of the winter’s overflow, which covers all the neighborhood for miles around.

“On one side of the island, exposed to the action of the waves, is a small cliff, in which the structure of the mound is displayed, and where it is seen that even to its base the earth is filled with pottery and ashes, proving the artificial origin of the mound. The waves have excavated very extensively into it, and the beach below is covered with the fragments of pottery.” (Derby 1879:225)

A number of American and Brazilian archaeologists visited Marajó in the late 1800s and early 1900s, publishing further brief descriptions of various sites and survey areas on the island. What they found there was a pleasant surprise. These mounds were full to bursting with artifacts left by a previously unknown archaeological culture, which was named -- somewhat unimaginatively, but what can you do -- the Marajoara culture.

The sheer number of mound sites across the island, and the extreme density of primarily pottery remnants found in them, attested to the presence of a large sedentary population in prehistory. The earliest and most complete description of the typology of these Marajoara finds can be found in Meggers & Evans (1957). The authors of this work provided some compelling evidence for the periodization of the Marajoara Phase of the island’s archaeological record. Starting in the 400s CE, there’s an apparent period of settlement intensification lasting into the 700s, followed by a pretty stable period where more localized traditions began to develop across the island. The decline of the Marajoara culture began in the 1200s, with a progressively larger number of sites turning up abandoned as time went on. By the 1400s, sites on Marajó attest the more or less total absence of Marajoara people, rolling smoothly into the succeeding Arua Phase, which has been connected to the migration of Arawakan speakers into the region.

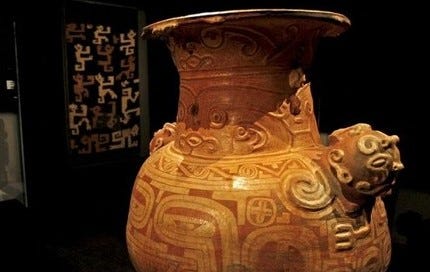

Worth mentioning here are the prolific and fascinating Marajoara pottery traditions, of which there were several occupying a generally similar stylistic mold. If you’re not a pot person, I think it’ll be useful to preface this with the clarification that Marajoara pottery is very impressive, not even just for the Amazon but from a global perspective. Marajoara pots are artfully decorated with generally abstract motifs painted and sculpted into them. Generally, everyday household ceramics appear to have been relatively simple in their construction and decoration. The really artistic items were what’s been termed funerary urns, which were large vessels, some in excess of 1 meter in diameter, used essentially as coffins in the burial of some (but definitely not all) Marajoara dead.

These urns were clearly extremely labor-intensive to produce, given their size, decoration, and the level of experience and knowledge that would be necessary to produce one. I generally dislike the tendency for archaeologists to say things like “the Marajoara clearly cared deeply for their dead” -- like, no shit, everyone does? -- but it’s clear that a lot of actual man-hours went into the funeral and burial of certain people in Marajoara society, and the inhabitants of Marajoara mounds placed a lot of value on the notion of living atop their honored dead (did I mention these urns were buried on the same mounds the Marajoara lived on?).

But clearly this herculean effort wasn’t exerted every time a Marajoara person died -- otherwise these mounds would be mostly corpses by volume. No, only certain people in Marajoara society were accorded the kind of respect that merited a full urn burial. Socially, it’s been argued that the Marajoara appear to have had a complex society, meaning there was social stratification between an apparently hereditary ruling class, a significantly larger but less powerful class of laborers, and possibly a class of specialist craftspeople who created all this beautiful and labor-intensive pottery (Meggers 1957:403). Backing up this notion is a constellation of material, skeletal, dietary, and geographic evidence, but I’ll just focus on one source of evidence for now: mound stratification.

You see, there are two general Marajoara mound types: small mounds under .2 hectares (averaging .078 ha at the Camutins site) and large mounds over .4 hectares (averaging .81 ha across a sample of 27 sites). There are very few mounds that occupy the space between those two ranges, indicating that the distinction was culturally important to the Marajoara. More importantly, this hypothetical distinction is supported by differences in the ceramic assemblages found at these two types of sites. Those amazing Marajoara funerary urns, for example, are only found on the larger mounds, while the remains of plainer pottery are found on both larger and smaller mounds. This distinction is so sharp that it led Meggers & Evans (1957) to classify the large mounds as ceremonial mounds and the smaller ones as habitation mounds, under the assumption that the larger mounds were used for elaborate burials and the Marajoara only actually lived on the smaller ones.

More recent excavations (Roosevelt 1991, Roosevelt & Bevan 2003, Schaan 2004) have confirmed that the ceremonial mounds were, in fact, inhabited throughout the Marajoara Phase, and were very densely populated -- though probably nowhere near as densely populated per hectare as the smaller habitation mounds, as I’ll discuss in a later section. Scholarship on the subject has lately come to rest on the conclusion that the Marajoara did exhibit social stratification, with the ceremonial mounds acting as the place of residence for elites and the habitation mounds being occupied by the low-status commoners.

And here we arrive at the main focus of this piece. All of this archaeological evidence -- the mobilization of large amounts of human labor for mound-building, the specialization of segments of the population for administration and pottery production, the sheer scale of existing sites and their occurrence in large numbers across the campos -- suggests that the northeastern part of Marajó Island was home to a large population throughout the duration of the Marajoara Phase. This population exerted significant influence over the environment, building large earthworks for habitation and, as Schaan (2004:165-7) argues, for exploitation of aquatic resources.

But what is a large population? Like … numerically? Well, let me tell you a story. When I was first researching this topic, long before I had either the inclination or the desire to write a piece on it, I skimmed through the Wikipedia article for “Marajoara culture.” In that article, I came across a claim:

“The pre-Columbian culture of Marajó may have developed social stratification and supported a population as large as 100,000 people.[1]”

I would like to preface this with a disclaimer: I love Wikipedia. Wikipedia is a gift to humanity, one of the noblest projects to have emerged out of the early internet era. Wikipedia is my mother, my father, my beloved child suckling at mine own teaT. But as my beloved child it’s more of a Tiny Tim type, sickly and bright, with occasional bursts of beautiful insight punctuating a pure but tragically childish naivete. I read something in a Wikipedia article and I’m off two hours later, still chasing that footnote into the wild blue yonder. But one must never, ever take something one reads on Wikipedia at face value. Because -- well, kids, let me tell you a secret. Wikipedia can sometimes be wrong.

100,000?? I mean, sure, it sounds like a lot of people. It’s roughly the population of South Bend, Indiana, one of the premier cities of North America. But the campos are pretty extensive, occupying about 20,000 km². I guess if 5 people per square kilometer counts as “large” to you, that’s your own business. But that’s fairly low for a premodern society, especially one that’s left behind so much in the way of material culture and earthwork construction. Based on what I’d seen at this point in my research, I didn’t believe it.

Where the hell had this claim come from?

The footnote led me to Charles C Mann’s 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, which is one particular entry in a long-running debate in prehistoric demography: how many people lived in the Americas before contact with Europeans? Mann falls firmly on the “fuckin’ TONS” side of the debate, so it’s a little weird that he’s advocating a position that would put the Marajoara cultural area at a population density roughly equivalent to, say, late medieval Scotland.

Unfortunately, some fetid piss-stain has had this book removed from the Internet Archive, the version on Open Library is preview-only, and my university library only has it in print. So I can’t confirm with 100% certainty where Mann got the cited number from, or if the cited number actually even appears in his book or not. Fortunately, I’m sufficiently knowledgeable about the topic of the Marajoara that I have a pretty good guess where it originated.

“A multimound site such as Os Camutins, which has 40 mounds of the Camutins Subphase, is likely to have had a population of more than 10,000 people. The prehistoric population density on Marajo would therefore have been very substantial. Based only on the published sites, the total population size could have been 100,000-200,000. This size range of population would give a population density of 5-10 people per square kilometer within the c. 20,000 km2 of the Marajoara domain. If reported sites are only a fraction of those that existed, the population could have been up to one million people, and the density could have been as great as 50 people per square kilometer.” (Roosevelt 1991:38)

So 100,000 is a minimum estimate, and makes a lot more sense in that context -- 5 persons per km² looks too low because it’s a lowball, it’s meant to. The number isn’t technically based on anything, but it comes with the full force you should assign to the personal opinion of a professional like Anna Roosevelt, who’s spent years in the field studying Marajoara sites. The actual range Roosevelt threw out there is between 100k and 1 million -- not totally useless, but not really very useful either. Especially given the fact that it, again, isn’t explicitly based on anything besides speculation.

At this point in the story, as I was sitting in the dark in my room, starving, unemployed, bitchless, something occurred to me. Why do we have to speculate? Don’t we already have enough information to make an educated guess?

My God. From my vantage point, stepped back from myself and the work I’d been doing, the whole Marajoara situation suddenly looked so flimsy and artificial and perfect. The demography of prehistoric societies is always a nightmare of educated guesswork because of all the unknowns in effect. Most of the trouble comes from the basic geography of human settlement; people like to spread out, to move around, to abandon settlements entirely for greener pastures. Archaeological remains are destroyed by natural disasters, buried under meters of sediment, grown over by forests or washed away by rivers.

And yet here, an arsenal of historical and environmental factors had converged to funnel the entire population of a recently-extinct society into a small number of sites that are all still there, very obvious, and relatively well-surveyed. We only have to ask a couple of questions to solve the problem:

How many large ceremonial mound sites were there?

What was the population density of the average ceremonial mound site?

What was the ratio of habitation mound sites to ceremonial mound sites?

What was the population density of the average habitation mound site?

How many of these sites were concurrently occupied?

Once we arrive at reasonable guesses for each of these variables, the question of Marajoara population becomes simple arithmetic. You literally couldn’t find an easier situation to do prehistoric demography for if you tried. With that in mind, the sections that follow are each themed after one of these questions, with a final two thrown in for conclusions and a brief discussion. Ready?

2. How many mounds?

So we know the area we’re looking at: the campos of northeastern Marajó, an area of about 20,000 square kilometers in total. And we know what we’re looking for: mounds, roughly circular or oval, 4 to 12 meters in height, with areas greater than .4 hectares. I assume, based on the archaeological evidence, that the smaller habitation mounds were politically and economically dependent on the larger ceremonial ones, so there should be a relatively consistent ratio between the two (I talk in Section 3 about how that assumption is borne out by the data). So the main task in this section is going to be arriving at a reasonable estimate of the number of ceremonial mounds over the whole Marajoara cultural area.

Man, the people I would kill for a LIDAR survey. But sadly, none are forthcoming on Marajó, so we appear to be left to our own devices here. This problem will have to be solved using the old-fashioned method: anecdotes, ground surveys, and extrapolation (the devil’s threesome).

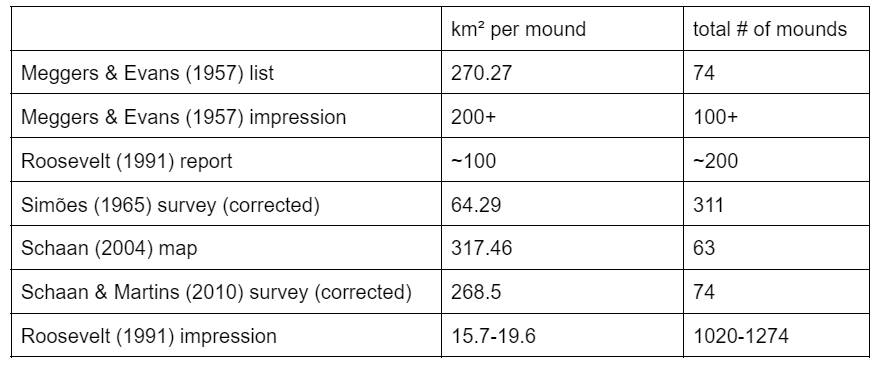

Right off the bat: there is no clear answer to the question “how many Marajoara mound sites are there.” There isn’t any central repository of information about these sites, and even if there were, sites are often known by multiple names or no name at all. The first published list of Marajoara sites in Meggers & Evans (1957:295-324) includes the names of 74 mounds, although the authors comment that “over a hundred” are known (id:295). Based on the measurements that are available, most of these appear to be the size expected of ceremonial mounds, although there are a large number of habitation-sized ones included. 35 years later, Roosevelt (1991:31-33) reported that “about 200” large funerary mounds are known, among about 400 total known sites. Schaan (2008:340), meanwhile, offers a map that identifies 63 mound sites, including several looted sites located in the northern part of the Marajoara cultural area (again, this includes several habitation mound sites).

So lists and reported figures are a bust. These numbers are not especially in sync with one another, beyond establishing a probable minimum of 63-74.

One potential fallback is extrapolating from mound densities established in field surveys of smaller areas. Simões (1965) surveyed a 450 km² area of Marajó and found 6 ceremonial mounds and 22 habitation mounds. Schaan & Martins (2010) appear to have surveyed the municipality of Santa Cruz do Arari, an area of 1,074 km², and found only 3 mounds of ceremonial size, alongside 12 habitation-sized sites and 4 sites whose measurements were not reported. If extrapolated to the whole Marajoara area, these mound density numbers would give us 267 or 56 total ceremonial mound sites, respectively.

Again, a fairly wide spread, complicated by the fact that both of those surveys are … well, they’re generally wrong. The Simões (1965) survey misses at least one mound from the map offered in Schaan (2008:340), and the Schaan & Martins (2010) survey lists no mound corresponding to the location or general measurements of the Ilha Pacoval mound from Derby (1879). I’m sure there are more of these little misses, but I don’t think collating all the various different lists from these surveys and every other literature review on the Marajoara is going to get us any closer to answering the question that headlines this section.

I’d like to leave off with a brief quote from Roosevelt (1991:33):

“My own experience has been that each documented Marajoara mound has near it three or four unreported sites, many of them modest habitation mounds of lesser elevation. Sighting from each substantial Marajoara mound, a person can see in a 5-kilometer radius around the site three or four other substantial mounds, many of them not recorded but known to the landowners and tenant ranchers.”

So we have the following candidate mound count estimates:

I mean … there’s certainly a range, right?

The Meggers & Evans (1957) list and the corrected Schaan & Martins (2010) survey outline our minimum -- 74 Marajoara mounds. Of course, the correct minimum is certainly greater than this number; these sources have clearly undersampled the total number of Marajoara mounds in their survey area. I think this is a problem inherent to list-type sources: new Marajoara sites are discovered and described relatively frequently, a dynamic that becomes even more pronounced the more in-depth the survey in question is.

Similarly, I feel pretty comfortable throwing out the impressionistic density estimate Roosevelt gives, which would give us a truly staggering minimum of 1,020 mounds. Obviously this kind of data can be valuable, but we shouldn’t follow it blindly, especially when it gives results like that. Probably Roosevelt’s impression is more accurate in the historically more densely-settled headwaters of the interior of Marajó, and shouldn’t be extrapolated to the whole Marajoara area.

And of course, similarly, the corrected Simões (1965) survey sampled an area that probably had a higher than average population during the Marajoara Phase, located as it was near the productive headwaters of two separate river systems.

Considering the numbers we have left, I’m comfortable arriving at a reasonable compromise minimum of 200 total Marajoara mound sites, or one mound site per every 100 km². I think this is a good middle ground within the huge spread of potential Marajoara mound density estimates, and will be going forward under the assumption that that’s the density we’re working with.

3. Teso dos Bichos, or: the population density of the elite mounds

So, we’ve constructed a reasonable estimate of ~200 Marajoara ceremonial mounds across the whole cultural area. Which, if we’re interested in determining total population, leaves us with a simple ask: how many people typically lived in one of these elite residence areas at any given time? This line of questioning will, of course, lead us to the archaeology of individual mounds. I’d like to start with the most well-surveyed of these, Teso dos Bichos.

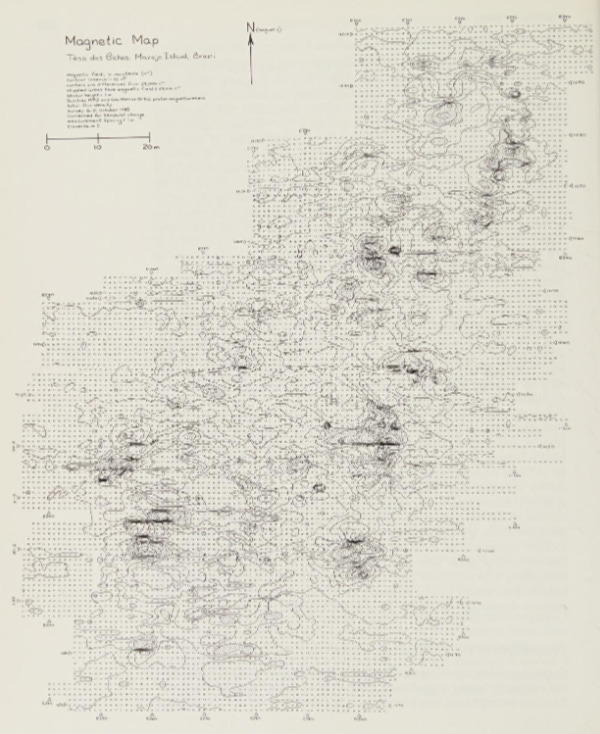

Teso dos Bichos is a large mound site located along the Goiapi River. It’s an oval-shaped mound about 7 meters in height and 140 by 60 meters in area. Significant parts of the surface of the mound have been eroded in the centuries since its abandonment, but the overall shape still holds.

Roosevelt (1991) summarizes the results of in-depth imaging and excavations conducted at Teso dos Bichos in the 1980s. For our purposes, it’s the imaging that concerns us the most. The survey team here used high-resolution magnetic imaging to map the entire mound for anomalies -- areas that have notably high or low magnetism compared to the surrounding soil. This is a method that’s been used profitably in other archaeological projects to non-destructively pinpoint manmade artifacts. Here, the goal was mainly to locate objects made of fired clay -- urns, hearths, etc. Ceramics and other earthen objects that have been exposed to high temperatures have a unique magnetic signature detectable in these kinds of ground surveys.

And oh boy, did they find a good few of these. The most striking result this survey found were these linear magnetic anomalies, which extended for several dozen meters in an east-west direction:

Excavation at a number of these linear anomalies determined that they represented large, linear groups of hearths: bowl-shaped ceramic stoves that were recessed into the ground, probably used for daily cooking purposes.

You can tell a lot about someone by looking at their kitchen. In this case, the layout of these hearth groups in distinct lines reveals that the Marajoara probably lived in multifamily longhouses, like many ethnographically known indigenous Amazonian peoples. All hearth clusters found at the site “occurred in large groups of 6 to 12 or occasionally more” (Roosevelt 1991:211). The east to west alignment of these hearth groups, and by extension the buildings they were likely located in, is a typical feature of a lot of tropical architectures; buildings that have the smallest possible cross-section facing the morning & evening sun tend to stay cooler throughout the day (Roosevelt prefers a ritual interpretation of this alignment -- 1991:338).

The footprints left by these long-gone longhouses will be our index for estimating the population of the mound at Teso dos Bichos. First off: in 11 test excavations, all excavated hearth groups were found at roughly the same archaeological level, implying that all of these longhouses were concurrently occupied. The magnetic imaging survey found 29 magnetic anomalies; subsequent excavation of 11 anomalies revealed all but one to be hearth groups. Roosevelt (1991:342) observes that 9 of these magnetic anomalies appear to overlap one another, indicating, despite the evidence for contemporaneity from the excavations, that these may represent structures that existed at different times. A reasonable minimum number of longhouses at Teso dos Bichos during the subphase investigated is probably therefore around 20.

How many people lived in each longhouse is less certain, but we can make assumptions based on the number of hearth groups per longhouse. Each hearth group is assumed to represent the food preparation space for a single nuclear family, so each longhouse would have served as the place of residence for 6-12 (or more) families (Roosevelt 1991:336). Comparable longhouse-type dwellings in ethnographically known Amazonian societies, called malocas, tended to house a similar number. Roosevelt prefers a range of 35 to 60, or an average of 50, individual inhabitants per Marajoara longhouse.

So we have our number. At Teso dos Bichos, there were likely between 700 and 1,200 inhabitants, with a reasonable middle-ground estimate of 1,000. And honestly, I wasn’t super shocked by that. Considering the sheer amount of surplus labor hours that would be required to build a mound 7 meters high and roughly .66 hectares in area (after hundreds of years of erosion!), I think anything less would be very weird.

4. Guajara, or: refining the estimates

If we assume that each ceremonial mound site represented a community of around 1,000 individuals, we arrive at an elite mound population of 200,000 for the Marajoara cultural area at the peak of the Phase. But there’s no call to be that hasty. Teso dos Bichos is only one site, and a single data point is nothing more than an anecdote -- not something a respectable Facts and Logic type draws a conclusion off of. This could simply represent an unusually densely-populated community. Or an unusually sparsely-populated one. Without further comparison with other sites, we have no way to know.

So where do we find more? Well, there are two other sites that I’d argue are sufficiently well-researched to merit basing a compromise estimate of elite mound population density off of. First, the team headed by Roosevelt also performed magnetic imaging of the site of Guajará, another large Marajoara mound located along the Anajás River.

Here, we have an issue, though: multiple published sources have advanced multiple interpretations of the data at Guajará. Roosevelt (1991:187) concludes, using the same methodology as at Teso dos Bichos, that the presence of 11 elongated east-west magnetic anomalies attests to the presence of 11 longhouse areas at Guajará, which would correspond to a capacity to house 440-550 inhabitants. However, in a later paper, she and a co-author employ an entirely different method, using the magnetic data to calculate the total number of hearths buried within the mound.

So the magnetic moment of the mound suggests 8,000 hearths (Roosevelt & Bevan 2003:10), which is then somewhat arbitrarily reduced to 2,200 hearths when far fewer are found in test excavations. Assuming a constant rate of replacement every 5-10 years, and continuous occupation of the mound during the 700-year period there are carbon dates for, the authors arrive at a population size of 78-156 people at Guajará.

I think I’m not being overly presumptuous when I say that this is a baffling replacement for a population estimation methodology that was totally fine as it was. There are just a huge number of assumptions underlying the “magnetic moment” approach -- that the mass of each hearth is predictable and consistent, that the replacement rate of hearths is unerringly once every 5-10 years, that the instruments used were able to detect hearths at every level of the site.

And unfortunately, because this paper spends so much of its oxygen on this thoroughly weird methodology, there’s not much discussion of the potential interpretations of the spatial layout of the geophysical data -- just counting hearths. What a wasteǃ

The kicker is, despite my clearly-expressed contempt for the methodology of this research, it would have arrived at numbers that are identical to the interpretation of the site in Roosevelt (1991) if the authors just hadn’t controlled for the lower number of hearths unearthed in their test pits and stuck with 8,000 hearths (translating to 283-567 inhabitants). Do you mind if I default to the standard 11-longhouse, 550-inhabitant interpretation of the results from the Guajará mound? No? Good. That’s what I’m doing.

The other mound I consider sufficiently thoroughly-surveyed to merit inclusion in the average elite mound density calculation is Camutins 17. This is a fairly small, roughly .17-hectare mound in the Camutins group, the largest known set of Marajoara mounds. The results of excavations conducted here are summarized in Schaan (2004:206). No imaging here; this team was raw-dogging it, just making test pits all around the site and recording what they found:

Now, the author concludes that there were 2 longhouses on the Camutins 17 mound. I would like to preface my objections with the fact that I am willing to accept this figure uncritically and will be incorporating it into the calculation of population density on the Marajoara mounds. However: looking at the survey maps, I can’t help but notice that there is a large patch of the mound where no test excavations were performed. A patch that would easily be large enough to hold a third longhouse. But I’m not comfortable incorporating that speculation into our final calculations.

So. We have our numbers for three elite mounds of wildly differing sizes and enthralling histories of study. Using these, we can construct an average for the density of longhouses per hectare, and therefore of inhabitants per hectare, that we could expect on any given Marajoara ceremonial mound:

At last, we have our hard-won average. Based on this sample, which is admittedly small but in my opinion fairly compelling, Marajoara settlements would have contained about 21 longhouses per hectare of mound space, or 1,050 inhabitants. Teso dos Bichos falls on the denser side of this distribution, while Camutins 17 falls on the sparser side and Guajará right in the middle.

5. Camutins, or: the habitation mounds

Here’s the rub, though: the elite Marajoara mounds, the huge ones with all of the ceremonial artifacts found on them, are only half of the story. Because the majority of Marajoara mounds are not elite mounds. Most Marajoara mounds lack the characteristic funerary ceramic assemblage and are significantly smaller, generally below .2 hectares in area. This fact comes to the fore when we focus down on some individual sites.

On the Camutins River, in the southwestern periphery of the Marajoara zone, we find the largest single Marajoara site so far discovered. Meggers & Evans (1957) documented 20 mounds here, and an additional 17 were recorded by Hilbert (1952). The most in-depth archaeological research on this site is contained in a 2008 PhD thesis by Denise Schaan, who counts a total of 34 individual Marajoara mound sites along this stretch of the river:

Immediately obvious just from this map is the fact that only 5 of these are the size we would expect of ceremonial mounds. And indeed, the ceramic assemblages discovered on these mounds bear that out. The large mounds are the only ones at Camutins that yield the striking Marajoara funerary urns associated with the society’s elite.

Other major multi-mound sites have a similar distribution: at the Fortaleza site, there are 13 smaller “habitation mounds” and 1 large “ceremonial mound” (Meggers & Evans 1957:295-324). Large mounds that aren’t part of multi-mound complexes, like Teso dos Bichos, are usually found in association with nearby small mounds, but it’s unclear precisely how close that association is (Roosevelt 1991:33). And if you thought finding numbers for the ceremonial mounds was a tough job, try these ones. They’re small, they don’t contain the impressive Marajoara funerary urns (which makes them uninteresting to many archaeologists), and they’re even more vulnerable to erosion than the taller elite mounds. The reason the numbers I mention above for the habitation mounds at Camutins don’t line up is probably because several of them were completely eroded away between Meggers, Evans, & Hilbert’s work in the 1940s and Schaan’s in the 2000s.

Generally, I’m favorable to the supposition that these smaller habitation mounds were politically and economically dependent on nearby elite mounds. This is reflected in the ceramic assemblages found at each type of site: the elite mounds have elite ceramics, while the habitation mounds simply don’t. It also squares with the differences we see in mound size: the politically and economically dominant inhabitants of the elite mounds probably achieved such large and impressive mound sizes by coopting labor from those that lived on the smaller mounds. Under this assumption, there should be a general ratio of smaller mounds to larger mounds that we can use to guesstimate the overall number of these smaller mounds in the Marajoara area as a whole.

Extrapolation is our friend here once again. We can use the ratios of habitation mounds to elite mounds found at these large, multi-mound sites to help arrive at an estimate of the overall ratio.

Unfortunately, the ratios we have are all over the place, and it’s not helped by the fact that our data is often spotty and incomplete. To help calibrate our estimate, we can also include evidence from the Simões (1965) survey and the impressionistic estimate given in Roosevelt (1991:33):

The spread is, again, pretty wide, but we’re closing in on something. For this project, I’ll be going forward with an assumption of 5 habitation mounds to every 1 ceremonial mound. I think this squares best with the available data, keeping in mind that Roosevelt’s and Simões are probably selection-biased (habitation mounds are significantly less topographically obvious than ceremonial ones, and so are less likely to be picked up in surveys and impressions alike).

But we’re not done here yet. There’s a further problem: the average habitation-sized mound across Schaan (2008) and Meggers & Evans (1957) is only about .077 hectares in size. That’s like, maybe the size of a football endzone. Under the longhouse:mound area ratios calculated using data from Teso dos Bichos, Guajara, and Camutins 17, that’s barely large enough to merit a single longhouse. About half of the mounds in the sample are smaller than even that. And yet clearly these sites were occupied. What gives?

Well, the obvious answer to this question is that the habitation mounds were likely significantly more densely populated than the elite mounds. This tracks with the overall impression that elite mound inhabitants were more economically and politically powerful than those of the habitation mounds, and enjoyed a higher standard of living in most ways. Where the elite mounds probably furnished their residents with open spaces, well-ventilated dwellings, and living areas raised high over the winter floodwaters (and any potential attack by residents of other mounds), the habitation mounds would have been extremely utilitarian, with probably just enough space for the footprints of one or two longhouses, and probably just enough elevation to avoid flooding during the winter.

Schaan (2008), under this assumption, calculated probable longhouse densities for the 32 habitation mounds at the Camutins site. Removing outliers, the average density of longhouse structures per hectare for these is 42.03 -- roughly twice as dense as the average longhouse:hectare ratio we calculated using data from the elite mounds. Our average habitation mound at this density would host about 3 longhouses, for a population of between 105 and 180 people (averaging 150).

6. How long?

We have most of our numbers squared away, but there remains a bit more to be settled. We could just multiply these numbers together and be done with it. But that would be assuming that all of these sites were concurrently occupied, at their maximum capacity, for at least some point in the Marajoara phase. Is this really a reasonable assumption to make?

Well, first off, use your fucking brain. You live in a place where the water level increases by 4 meters every winter, and basically the only spots that are livable during that period of inundation are these anthropogenic mounds. Where are you going to build your house? There’s a clear and obvious combination of push and pull that would have inevitably driven the people of the Marajoara culture to inhabit these mounds, and that’s something that’s absolutely reflected in the archaeological record.

Is there evidence of mound abandonment? Absolutely. In the stage that preceded the Marajoara, called the Formiga Phase, there are some clear indications that the people of the area were only just beginning to experiment with life in the extreme environment of the campos. And this is reflected in an abundance of Formiga Phase mounds that were built in disadvantageous places, mostly in the far southwest of the plains, and subsequently abandoned. And some of this mound abandonment spills into the very early Marajoara Phase; one site, Cabecera de Camara, shows evidence of abandonment around 600 CE. However, this is the only evidence of mound abandonment I’ve seen dating to this period; the data from Marajoara mounds indicates that most were inhabited for basically the entire Phase.

There are 16 radiocarbon dates available from Teso dos Bichos, ranging from 695 to 1400 CE, with no significant gaps in between (Roosevelt 1991:313-4). The situation is similar for Guajara, with 3 dates from 615 to 1275 CE (Roosevelt 1991:314). Relative dating of material from the Camutins 17 mound indicates occupation from 400 to 1320 CE (Schaan 2004:198). It appears that, after an initial wave of mound-building that swept northeast over the campos between 400 and 700 CE, mound habitation remained basically stable until the late 1200s, when abandonment of mounds began to occur and the Marajoara Phase entered its terminal period. With that in mind, there’s no reason to assume that mound occupation rates at the peak of the Marajoara period in the 700s-1100s did not approach or meet 100%.

7. Putting it all together

So. We have our numerical guesstimates for the overall number of elite and habitation mounds. We have our more mathematically-determined ranges for the population densities of both. And we’ve determined that, at the height of the phase, pretty much all of the known Marajoara sites were occupied concurrently. It’s time to put it all together, finally answer the actual question we’ve been angling at this whole time -- how many Marajoara?

Great!

So … where does that put us?

Well, at this level, the population density of the Marajoara area at its peak in the 1100s would be around 16.54 persons per square kilometer. That’s roughly comparable to the population densities achieved in fairly populous European countries like France (20 per km²) and Spain (17.79 per km²) around the same period. Notably, it’s also very close to an estimate given by William Denevan, a historian interested in the pre-Columbian demography of the Americas, for the average population density of lowland Amazonia in the 1400s (18 per km²). More on that later.

So that’s the end of the storyǃ We have our conclusive answer for the question of Marajoara population. I personally think it’s extremely ironclad. Surely there is nothing that we have missed, no vital puzzle piece lying abandoned on the ground. Huzzahǃ

8. Cacoal, or: dark matter

From the Camutins site, take a trip downriver a ways, in a southwesterly direction towards the forested half of the island. You’ll probably be able to see the Pequaquara and Monte Carmelo mound groups in the distance, but that’s not where we’re headed. Here, along the banks of the Anajás River, you’ll come upon a Marajoara archaeological site. One that is not located atop an anthropogenic mound.

This site, Cacoal, is one of four non-mound sites so far discovered along the lower Anajás River (Schaan 2000:469). It’s clearly Marajoara, bearing ceramics that fall into that recognizable type, and yielding radiocarbon dates that situate it between 700 and 1100 CE, the height of the Marajoara Phase (Schaan 2004:143-4). And Cacoal is not an outlier.

“Though it is sometimes said in the literature (Willey 1971) that all Marajoara sites are artificial mounds, there are many non-mound Marajoara sites, especially in the gallery forests along rivers and ancient levees. Earlier investigations at such sites and our reconnaissance at Ilha dos Marcos show the non-mound sites to have wide areas of black soil garbage. During the reconnaissance survey carried out in preparation for the systematic survey, we have recorded several new non-mound Marajoara sites in gallery forests, and there are many small mounds that are not mentioned in the literature. The low mounds and non-mounds seem more numerous than the tall mounds, but received less attention until professional archaeologists began working in the area in the late 1940s.” (Roosevelt 1991:33)

In a word: shit. This throws a wrench into one of the fundamental assumptions of this project: that the population of the Marajoara culture can be easily estimated because nearly all inhabitants lived atop the obvious and recognizable mounds. If you’ll forgive the metaphor, non-mound sites like Cacoal introduce a kind of dark matter into our demographic calculations. We know that, during the peak of the Marajoara Phase, there was a subset of the population that lived at these non-mound sites, likely full-time judging from the density of archaeological finds at places like Cacoal. This means that any estimate of population we come up with will certainly be an underestimation of the actual number of people living on the eastern half of the island during this period.

And here we come to a confession that’s been a long time coming: so far, at every juncture in this project, I’ve opted for the interpretation that advances the most conservative reasonable estimate for the peak population of the Marajoara area.

In developing my estimate for the number of elite mounds, I went for 200 despite the higher number of 311 suggested by extrapolation of the Simões (1965) survey and the significantly higher 1020-1274 drawn from the impressionistic estimates in Roosevelt (1991). I did this not because these estimates are unreasonable or not valuable, but because 200 was the lowest estimate that wasn’t completely infeasible given the available data.

In estimating the population density of the elite mounds, I incorporated the Schaan (2004) estimate for the number of longhouses on the Camutins 17 mound despite my misgivings about the methodology involved. I also used 20 longhouses as the number for the Teso dos Bichos mound, despite the lack of concrete archaeological evidence supporting that reduction from the 29 magnetic anomalies detected at the site.

In estimating the number of habitation sites per elite site, I went for a number that mostly ignored the documented effects of erosion and site selection in biasing results. To be honest, in my heart of hearts I believe a ratio of 6-7 habitation mounds to every 1 elite mound, as seen at the Camutins site, is closer to the truth.

And finally, I choose to ignore the certain truth that there was a portion of the Marajoara population occupying sites that were not located on anthropogenic mounds. There’s obviously the issue of calculating this population -- how would you even begin to approach that kind of problem? -- but more to the point, it isn’t in the spirit of this exercise. Because what we’ve been determining here isn’t a hard and fast “likeliest peak population” of the Marajoara culture. What we’ve been determining here is a minimum.

There’s very little in the way of argumentation that could support a number of less than 330,960 inhabitants of the Marajoara culture at its peak. My opinion is that any number lower than that is simply untenable, requiring at least one manifestly unreasonable interpretation of the archaeological data. For example, you could argue that the number of mounds attested in list-type sources like Meggers & Evans (1957) is actually a good estimate of the total number of mounds occupied at the culture’s height. However, this would run completely contrary to the opinions of experts in the field like Roosevelt, who state that there are many mounds not listed in published archaeological work, and it would not square with the recent discoveries of new Marajoara mound groups not listed in these sources, like the Pequaquara multi-mound site first recorded in Schaan (2000).

On the flip side, there are very good arguments that could be marshaled in support of the idea that the population of the Marajoara culture was significantly greater than 330,960. In fact, I think it’s more or less certain that it was.

Using the numbers I personally find to be most reasonable, I tend to arrive at a peak Marajoara population of around 600,000 mound-dwellers plus an unknown and probably unknowable additional population of non-mound-dwellers, yielding a population density of over 30 inhabitants per square kilometer. But I understand that the decisions that lead me to choose those numbers over others are largely subjective. Feel free to engage with the data and construct your own interpretationsǃ But keep in mind the hard and fast minimum we’ve calculated here. There is very little likelihood that the population of eastern Marajó in the 700s-1100s was lower than 300,000 inhabitants.

9. Meaning

If there’s one thing I find myself really disliking, it’s historical narrative. In my experience, human beings are chaotic and messy people, and it’s very difficult to pin our aggregated behavior down into neat stories without flattening out most of what makes us interesting, unpredictable. Unfortunately, I find myself writing on a topic that has a place in a narrative, for better or for worse. Here is my attempt to situate it therein.

Currently, there is a debate raging in historical circles about the demography of the Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans. On one side, there are those who contend that the continent’s population density was significantly lower than those of contemporary societies in Europe and Asia. On the other side, there are those who contend that its population density was similar to those societies’ or higher. If you pay close attention to the debate, you may notice that the former tend to situate their arguments in ethnographic evidence from North America, while the latter tend to rely more on accounts from the Andes and Mexico. Both sides regularly arrive at conclusions that the other find patently absurd.

You may also notice that, until very recently, the Amazon remained at best a footnote in this debate. Occasionally, those on the Big Population side would cite the voyage of Francisco de Orellana, the first European to traverse the length of the Amazon River in 1541-42. De Orellana described seeing massive settlements along his route, cities with standing armies, road networks, social stratification, autocratic rule. When the Spanish and Portuguese began revisiting the Amazon decades later, they found none of it. Further explorations by Europeans into the Amazon revealed societies with a local level of organization, a low degree of social complexity, and a lack of significant impact on their environment.

But the evidence that de Orellana’s observations were based in fact has continued to trickle in. For hundreds of years, people have been finding large, localized deposits of anthropogenic black soil, terra preta, in the ordinarily clayey and poor-quality earth of the Amazon. More recently, archaeological investigations employing LIDAR have all but confirmed the existence of massive earthworks in the region, indications of human settlements on a scale that can really only be described as urban.

On the Big Population side of the debate, this has galvanized a reinterpretation of the prehistoric demography of the Amazon Basin. Denevan (2014) suggests a population density of 18 persons per square kilometer over the Amazon floodplain region, a number equal to or greater than that of contemporary societies in Europe and parts of Asia.

Bringing things back to the Marajoara. The evidence presented here suggests that, at the peak of the Marajoara Phase in the 700s-1100s, Marajó Island was home to a group of societies that exhibited social stratification, specialization, and a high degree of collective decision-making, achieving population densities greater than 16 inhabitants per square kilometer. And yet, this recent archaeological evidence from other parts of the Amazon Basin suggests that the Marajoara were not exceptional for their region. Far from it -- the mobilization of labor required to build the elite mounds of Marajó looks almost quaint compared to the massively larger efforts that would have gone into many of the earthworks now being uncovered in Bolivia and parts of Brazil. If a society’s ability to mobilize labor for construction projects correlates with population density, and the Marajoara, with their population density equal to or greater than that of contemporary Old World societies, were less able to do so than their counterparts in other areas of the Amazon … what kind of populations existed in those areas?

Again, I dislike historical narrative. But fuck me if that isn’t a compelling one.

References

Bevan, Bruce W., & Anna C. Roosevelt. 2003. Geophysical exploration of Guajará, a prehistoric earth mound in Brazil.

Denevan, William M. 2014. Estimating Amazonian Indian Numbers in 1492.

Derby, Orville A. 1879. The artificial mounds of the island of Marajó, Brazil.

Meggers, Betty, & Clifford Evans. 1957. Archaeological investigations at the mouth of the Amazon.

Roosevelt, Anna Curtenius. 1991. Moundbuilders of the Amazon: Geophysical archaeology on Marajo Island, Brazil.

Schaan, Denise P. 2000. Recent investigations on Marajoara culture, Marajó Island, Brazil.

Schaan, Denise P. 2004. The Camutins chiefdom: Rise and development of social complexity on Marajo Island, Brazilian Amazon.

Schaan, Denise Pahl, & Christiane Pires Martins. 2010. Muito além dos campos: Arqueologia e história na Amazônia Marajoara (in Portuguese).